THE 40 DAYS OF GB5QM/MM

by Al Lee, W6KQI

Sun City, Arizona

The Queen Mary embarked on its ultimate voyage amid worldwide

fanfare and the accompaniment of Amateur Radio.

TO commemorate an historic event, a quarter of a century ago,

a group of hams from southern California took on what may have been one

of the greatest projects ever undertaken by an Amateur Radio club. When

the City of Long Beach, California, purchased the luxury liner the R.M.S..

Queen Mary from the Cunard Lines in 1967, it was decided to allow passengers

on her final cruise from Southampton, England, to Long Beach, California.

Nate Brightman, K60SC, came up with the idea of putting a ham station aboard

the mighty Queen. He convinced the Board of Directors of the Associated

Radio Amateurs of Long Beach (ARALB) to allow him to start the wheels turning

for whatever it would take to set up and operate a special-event station

to publicize the city's purchase of the ship and how it was to be used

as a tourist attraction. I booked passage, as did club members Ray (W6HO)

and Jean (K6TUE) Harter, of Long Beach. Ray agreed to be a station operator,

as did another passenger, Walt Barnes, W6IMK of San Gabriella California.

Following the public announcement of our project, Herb Johnson, W6QKI

of Swan Engineering in Ocean side, graciously provided us with two Swan

500 HF transceivers and other equipment, including a Swantenna mobile antenna

and a special attachment for mounting it on the ship's rail. The ports

of call included Southampton; Lisbon, Portugal; LAs Palmas, Canary Islands;

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Valparaiso, Chile; Callao, Peru; Balboa, Canal

Zone; Acapulco, Mexico; and Long Beach, California. The trip was made around

Cape Horn on the southern tip of South America because the ship is too

large for the Panama Canal.

Problems and Solutions

It was touch and go for a while, but with Nate's persistence and

the cooperation of the U.S. State Department, the ARRL, the British

General Post Office (GPO) Communications Department and Cunard Lines, the

issuance of special-event call sign GB5QM was authorized, pending inspection

of our station on board the Queen Mary prior to departure. After an interesting

trip to Southampton via London, I obtained permission to go aboard

before most of the passengers arrived. I met the First Electrician, who

reminded me that the ship's power is 200 volts DC. I asked him if

he could help me obtain 115 volt, 60-Hz AC. He had a husky motor-generator

on wheels in his shop with a 200-V dc motor connected to a generator

that put out 115-V, 60-Hz AC, and he asked me if I'd like to use

it. I was slightly over-whelmed by the question, but expressed my appreciation,

and soon it was installed in a fan room and wired to the cabin we were

to use as a radio room. Soon after going aboard the Queen and trying

to get the gear set up and the antenna installed, I was met on deck

by Eric Godsmark, G5CO, Chief of the Communications Department of the GPO,

and two inspectors. They were right on schedule, but had arrived

less than one hour after I had started to unload the boxes and set up the

station. I apologized for not being ready and Godsmark graciously said

he'd return in the afternoon. The two inspectors offered to stay and help

me with the installation. What a wonderful gesture on their part. They

stated that they had tremendous interest and curiosity in what I was doing

and couldn't believe that hams could own such sophisticated equipment.

Soon Godsmark returned and the station was ready.

|

| VINTAGE RADIO: What display on the Queen Mary gets more eyes

to sparkle than anything else? The radio room, where interesting sounds

flow from people stop to wander in and ask questions. Some visitors are

just fascinated to look at the radios and daydream about what it might

have been like to communicate by radio from a faraway ocean. What ham wouldn't

enjoy a radio contact from the Queen Mary? That's what OEX Editor Jon Bloom,

KE3Z , and ARRL Educational Activities Department Manager Rosalie White,

WALSTO, got to try their hands at during a shipboard visit with Nate Brightman,

K60SC. The operators on the other end are always excited to find out it's

the Queen Mary they've reached. |

Then the first problem arose: To tune the Swantenna, you start on 3995

kHz and tune the extendible top section for maximum RF, as read on a field

strength meter. To change bands, though, requires 12 V DC, but all I had

were 220 VDC, 115 VAC and 12 VAC. Buchan said, "I have an 18-volt battery

in my walkie-talkie. Let's try that". So out it came and I clipped it into

the circuit and it worked. Now I was on 75 meters, but British hams

can't go above 3800 kHz and the antenna first has to be tuned on 3995.

So, with the head of Great Britain's communications regulatory agency sitting

next to me, I explained the procedure and asked if I might make a brief

transmission on 3995. He seemed to be enjoying the whole thing so much

that he said, "Certainly, go right ahead. " After peaking the antenna on

3995, 1 switched to 20 meters. Meanwhile, as I tested, Buchan needed his

battery back to communicate with the other inspectors on board. They were

looking for RFI to the ship's communications, PA and intercom systems while

I transmitted. Each time I needed to change bands, out came the battery

from his hand-held. I was given a clean bill of health by the inspectors,

and Godsmark stated, "Now, I have the unpleasant duty of asking you for

six pounds ($16.80 US at that time), in exchange for which I will issue

to you this licence, authorizing you and your fellow operators to operate

GB5QM/MM (maritime mobile) and GB5QM/MA (maritime at anchor)" He then endorsed

the 16-page document with "Signed on behalf of Her Majesty's Postmaster

General, C. E. Godsmark." Godsmark declared that I was not only the

"first American ever to be licenced to operate a station on a British vessel,

but it was the first time a VFO was to be used to control a maritime transmitter."

For this reason, he wanted to check the nature and design of the equipment

personally. He then stood up, shook my hand and said, "Cheerio, Mr Lee,

and good luck on your trip." I was so dumbfounded that I forgot to present

a gift package to him on behalf of our club.

Departure Day: October 31, 1967

Sailing from Southampton was a truly moving event. As the tugboats pushed

the giant liner out into the Solent River, the band playing Auld Lang Syne

began to fade. As we got underway with our own power, the Royal Navy flew

a group of helicopters overhead in the formation of an anchor. Even though

it was a regular working day for most everyone on shore, there were more

than 10,000 Britons who came to Southampton to bid the Queen Mary farewell.

All ships sounded their horns and dipped their flags to half mast as we

passed. The following day, I met with the other two operators

and we agreed on a tentative operating schedule. Our fourth operator, Buz

Reeves, K2GL, from Tuxedo Park, New York, made his appearance later.

Buz had brought his own equipment aboard to operate from his cabin on "A"

Deck. The GPO and the ship's communications officer didn't quite

go along with this, so Buz came to my cabin to offer, and was later given

approval by the GPO, to use our call sign, GBSQM, on 10 meters (his logs

were to become our property). His assistance was greatly appreciated, as

he turned out to be a terrific operator. The station was licensed to operate

in England (/MA), on the high seas and later in US territorial waters,

but before arriving at each intermediate port, we had to turn everything

off and become tourists.

Touring the stopovers are stories in themselves. We wanted to operate

the station as much as possible while at sea. We had antenna problems from

the beginning, so the decision was made to make 20- and 15-meter dipoles

from whatever material was available aboard ship. Wire was plentiful, but

when I asked the First Electrician for something to use as a center insulator,

the smallest ones he could offer were 10 inches long! For feed line, there

was a large supply of British 850 ohm TV receiving coax. It went together

easily and with a little pruning we got them to resonate within the bands.

What a time for the band to be dead. Ray called CQ for more than

two hours without an answer.

After dinner, it was back to the shack. This time, 20 meters was open

and the pileup began. For four hours, I worked lots of stations and was

thankful when Walt relieved me at 2330 local. While operating near the

southern part of South America as we approached Cape Horn, I worked Don

Wallace, W6AM, in Palos Verdes, who was using his famous rhombics, and

I contacted Herb Gleed, W6FQ, in Los Angeles, of QCWA Net fame. I apparently

gave Gleed a better report than I did Wallace, which must have excited

him, because Gleed still likes to remind me of this when we have an eyeball

QSO or work each other on the air. Rounding the Horn was a memorable occasion,

but I did more sightseeing than operating until clear of the cape. Band

conditions were good for most of the remainder of the trip. We were frequently

put off the air by the ship's chief communications officer, though, because

we apparently interfered with the ship's communications while they were

handling commercial traffic. It was frustrating, but at least he was polite

about it and we were compelled to cooperate.

|

| WHAT A QSL: Hams who contacted GB5QM received this impressive

81/2- x 1 1 -inch color certificate commemorating the Queen's final voyage,

courtesy of the ARALB. The color separator who worked on the artwork for

this certificate, Bob Spiegel, became intrigued by the operation and eventually

became a ham himself, WB6ILM. |

Saturday, December 9

We passed San Diego as the final day of the cruise dawned. I talked

with hams along the coast who said the Queen looked quite beautiful against

the rising sun. The seas were rough and the wind was bitter. It was the

first cold weather since crossing the equator. I wished I hadn't packed

away my topcoat and gloves. Our club president, Walt "Mac" McClellan, WB6NQU,

of Bellflower, California, went aeronautical mobile to view the Queen and

take pictures. I worked him part of the time, but calls were coming in

from all over. The pilot was famous aviator Fran Berra, and she had difficulty

finding the ship for a while. I got run off the air again, so I shut down

the station, grabbed my cameras and photographed the reception in Long

Beach. Off Huntington Beach, we were met by hundreds of boats. By the time

we reached Long Beach, there were more than 1000 boats to greet us as we

sailed slowly past Long Beach to Point Furman, then came about to steam

through Angel's Gate. The boats lined up on both sides, but gave us a clear

path to the pier for docking.

By late afternoon, I went ashore, leaving the gear on board, and found

my luggage. I cleared customs in a tent set up especially for the occasion.

Next, I found my family, and Nate and his family, and off we drove. Home

again.

December 10

It was my responsibility to get the gear off the ship and return it

to Swan Engineering in Oceanside. I was able to go aboard and tear down

the station, repack it and remove it from the ship. Before disconnecting

though, I put out a few CQs using the call sign GB5QM/6 and had few responses.

The excitement of working this rare station was over.

Post Mortem

As a result of this special voyage, I met many fine people and established

lasting friendships. We made more than our expected number of contacts

- after all, GB5QM was never advertised as a DX-pedition. For years afterward,

Nate and I visited radio clubs to present our story and slide show. It

was always a pleasure to make these presentations. Nate continues to direct

shipboard operations on the Queen Mary on behalf of the 250 member ARALB,

and established club station W6RO, which operates today. He's ably assisted

by Bill Holder, W6TNB, and by Bob Hennessy, WD6AVW, head of the 10-person

QSL Committee.

R.M.S. QUEEN MARY - Grand

Lady of the Seas

One of the world's legendary superliners, the RMS Queen Mary's

keel was laid in December 1930 by John Brown & Company Ltd at the Clydebank

shipyard in in Scotland. Workers installed more than 600 telephones, 700

clocks, 2000 glass portholes and 5000 chairs, sofas and tables. Named by

Her Majesty Queen Mary at the shipyard on the River Clyde on September

26, 1934, the opulent ship was launched at Southampton, England, although

her official homeport was Liverpool. Her maiden voyage began May 27, 1936,

as she sailed to New York City. In her heyday, she was a massive and impressive

monument to maritime luxury. When placed in service, she was the world's

largest liner. Able to make better than 30 knots, the 81,200 ton three-stacker

was the world's fastest ocean liner until 1952. She measures 1018 feet

from stem to stern with a 119 foot beam, 200 foot foremast, four 35 foot

propellers and two 16 ton bow anchors on 900 feet of chain weighing 45

tons. She draws 39 feet of water and has accommodations for 1957 passengers

to sail in high style, with a crew of 1174. The ship has 12 decks, including

a 724 foot promenade deck, and carried 24 diesel powered lifeboats. Her

luxurious main lounge is three decks high and 96 feet long. The Queen Mary

had the most successful career of all the superships. She made 1000 North

Atlantic crossings and carried two million passengers in 31 years of service.

She earned $600 million for the Cunard-White Star Line.

During WWII, she carried 765,400 military personnel (as many as 15,000

at a time), and 12,800 GI brides and children, logging 569,400 miles through

dangerous wartime seas. As with all British cruisers, the Queen Mary's

communications equipment and radio officers were leased to the shipping

line by the International Marine Radio Company. The ship's call sign, GBTT,

has been reissued to the Queen Elizabeth II. The extensive onboard collection

and display of vintage radio equipment includes a complete spark gap station

and a duplicate of the radio used on the Titanic. John Porter, WA6TNK,

is responsible for the antique wireless exhibit.

|

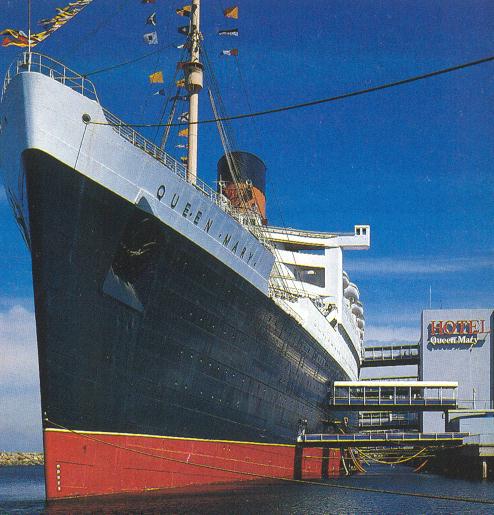

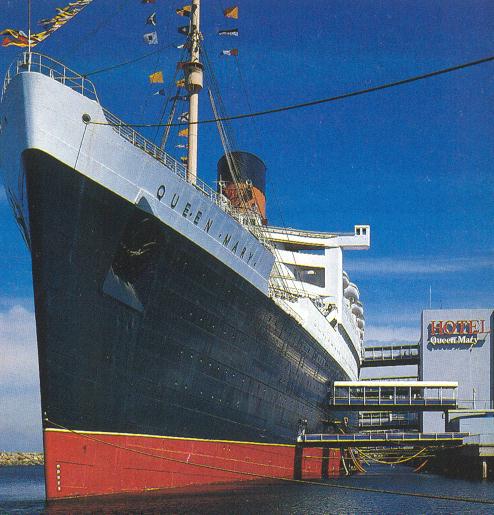

| TODAY: The Queen Mary as she appears after her conversion to

a hotel and convention centre. (Queen Mary Promotional photo). |

Operated as a hotel, restaurant museum and tourist attraction

by the City of Long Beach since about 1969, the Queen Mary was taken over

by the Port of Long Beach in 1978, which financed the restoration of the

original wireless room and made accommodations for a ham station. The head

of the Queen Mary Department of the City of Long Beach, John McAdams, became

so interested in the amateur operations that he subsequently became licensed

as KI6AV. The Port leased the ship to the Wrather Corp in 1979, and it

was that year that W6RO went on the air. In 1988, the Wrather lease was

purchased by the Disney Company, which wanted to remove the ham station.

Nate Brightman, K60SC, who had established the ham operation and ensured

that the station would carry a million dollars' worth of ARRL liability

insurance, convinced the Harbor Commissioners to issue a special permit

to authorize the station to continue operating from the Queen Mary indefinitely.

Disney's lease has expired, and at the beginning of 1993 the ship goes

back under the authority of the city of Long Beach, which will select a

new operator. The lively radio room is a highlight of the Queen Mary tour,

and its operators are happy to chat with anyone who stops to look in through

the Dutch doors. If a visitor happens to be a ham, he or she is invited

to sign the guest book and get on the air. Guest ops receive a handsome

certificate. Brightman estimates that more than 2000 hams stop by each

year. To visit the Queen Mary, take the Long Beach 710 Freeway to

the end (south from LA) at Pier J. A nominal fee is charged for adults

and for parking. For information call 310-435-4747. Bring your license.

Via QST Magazine , December 1992

Return to Radio Reading Room