|

| AT HOME: Here the John Brown is berthed at her home port of Baltimore, Maryland. She is a living memorial to all the merchant seamen, armed guards and shipyards workers of World War II. (Postcard photo by Ray Brubacher). |

The day had been long anticipated, but August 6, 2000 finally arrived. It was to be the day when I first set foot aboard the S.S. John Brown, one of only two remaining operational Liberty ships left in the world. After a record breaking summer of rain, it was no surprise that I would be greeted with a cloudy, overcast sky and a prediction of rain but that certainly wasn't going to put a damper on my spirits. It did cause the cancellation of fly-bys by W.W.II aircraft; luckily the rain held off for the entire voyage.

|

| AT HOME: Here the John Brown is berthed at her home port of Baltimore, Maryland. She is a living memorial to all the merchant seamen, armed guards and shipyards workers of World War II. (Postcard photo by Ray Brubacher). |

The immense size of this cargo vessel quickly became apparent as I approached her accommodation ladder. She is 441 feet long, with a beam of 57 feet, a draught of nearly 28 feet (fully loaded) and a deadweight tonnage of 10,865 tons. During W.W.II, 2700 of these ships were built under the designation EC2-S-C1 and their official name was “Maritime Commission Emergency Cargo Ship”. For the first time, mass production techniques were applied to shipbuilding. One of the sobriquets acquired by these ships was “ built by the mile, chopped off by the yard”. The all time record for building a Liberty ship was one week – from the time her keel was laid until the moment she had steam in her boilers. The Brown, built by Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard in Baltimore, Maryland, was completed built in 54 days and delivered to the U.S. government on September 19, 1942 at a cost of $1,750,000. During W.W.II, Liberty ships were operated by the War Shipping Administration and Army Transport Service. Their anticipated life span was only five years, and so great was the expected casualty rate that the U.S. Navy considered one safe voyage per ship a full quota. The Brown required a crew of 45 merchant seamen and 41 Naval Armed Guard during wartime.The John Brown was in Toronto on the last stop of her Great Lakes 2000 tour after sailing to Toledo Ohio to have 15,000 hull rivets replaced below the waterline. Because today’s ocean going vessels have welded rather than riveted hulls, there are no working rivet gangs left in eastern US shipyards. On the Great Lakes however, there are still a fair number of ships with riveted hulls, hence the availability of riveters in Toledo. To have the Brown (whose home port is Baltimore, Maryland) come up the Great Lakes for this work, the cost for fuel and lubrication alone worked out to $US 25 per mile and the money had to be acquired by fundraising.

Once aboard, I headed to the #2 tween deck where all the passengers enjoyed a continental breakfast. This area of the ship also contains the Armed Guard Museum. Liberty ships and other American merchantmen were crewed with merchant seamen but it was the Navy who operated the armament. Because the John Brown was a troop/cargo ship, she carried more guns that the standard Liberty ships – a total of 12. Included in the armament were combinations of 5” 38, 3” 50 guns and 20 mm Oerlikon machine guns. The Brown’s troop capacity was 500 soldiers.

I then paid a visit to the radio room and noted details about the vintage radios fitted aboard the ship. One minor disappointment was the lack of a “docent” radio operator who could interpret the use of the equipment during W.W.II. Next, I noted large amounts of cracked material surrounding the sides of the gun tubs and deckhouse. This is called “plastic armour” and was made from a mixture of Trinidad asphalt and stones. It was heated to 600 degrees F before being poured into moulds on the ship. During the war, plastic armour replaced steel armour plate, which was in short supply. This material helped to protect the bridge and radio room from enemy bullets or shrapnel. The photo at the left illustrates the fitting of the armour around the bridge and gun tubs. (Photo by Jerry Proc).

By 10:00 we cast off and the excitement began. The Brown’s Toronto voyage had a distinctive Canadian spin added to it. Entertainment throughout the day was provided by HMCS York Naval Reserve Unit Band. Frank Moore of HMCS HAIDA arranged for a W.W.II jeep to be hoisted aboard and displayed at the ship's brow. This jeep is the property of The Ontario Regiment Museum (ORM) in Oshawa Ontario and was used by Colonel Ward Irwin, commander of his (Ontario Regiment) unit in Sicily and Italy. The jeep was assembled by members of his unit from two damaged vehicles and was in service until Ward was wounded in action. The vehicle was subsequently shipped back to Canada and presented to Ward at his home in Whitby, Ontario by his former driver. The ORM restored the Jeep at the request of Mrs. Ella Irwin, widow of Ward Irwin, and subsequently was donated by her to the museum. The photo at the right shows the jeep being hoisted aboard the John Brown. (Photo by Frank Moore).

Also aboard were members of the Museum of Applied Military History (a reenactment group) dressed in W.W.II period uniforms. Units represented, included the Royal Canadian Navy, Womens Royal Canadian Naval Service, 1st Canadian Parachute Regiment, Perth Regiment, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, Canadian Womens Army Corps and the US Army. These reenactments were staged during the weekend to add to the nostalgia of the event. They also acted as tour guides and manned the guns for the anticipated attack by “enemy” aircraft. During the cruise, an original W.W.II backpack radio set (Wireless Set No. 48) was used to make Morse code contact between the SS John W. Brown and HMCS Haida by David Lawrence, VE3ORP a retired Major from the RCAF (Air Defence Radar and Signals Intelligence). The deck activity throughout the day is best is expressed in the photo of at the left. (Photo by Jerry Proc).

Aircraft from the Canadian Warplane Heritage and other groups were expected to fly past the ship and demonstrate combat operation. Gas operated (propane) guns on the Brown’s bow would shoot at the “attackers”. Unfortunately the horizontal and vertical visibility required for VFR (Visual Flight Rules) did not meet requirements, so the aircraft remained grounded. Aft of the bridge superstructure, Mr. Conrad Milster, Chief Engineer of the steam plant at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY, demonstrated various types of steam whistles, mainly from ships but at least one from a locomotive. All of the whistles were operated through a manifold connected to the Brown’s steam supply.

On a more serious note, a memorial service was conducted to honour all those men who served in the merchant navy during W.W.II and especially those who made the supreme sacrifice. After the service, anyone who served on any merchant vessel during W.W.II was welcomed into #4 cargo hold for a group photo. It was also an appropriate way to pay respect to all of the gallant merchant mariners who served aboard the Liberty, Victory, Park and Fort class ships (and any other merchantmen). Let us take a moment to remember.

IN REMEMBRANCE

They shall not grow old,

As we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them,

Nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun

And in the morning we will remember them.

After being served a delicious, all-you-can eat buffet around noon, I wandered over to the lineup for the engine room tour. This was the absolute highlight of the day – to see a live, triple expansion, marine steam engine at work. While waiting for the lineup to move, a Brown crew member entertained us with Liberty ship trivia. For instance, all machinery on board is operated by steam. When the ship is in the dockyard, ancillary equipment in the engine room is flashed up with compressed air. Once the fire was up, it was then expected that the ship would keep at least one boiler lit at all times. Should steam be lost under any circumstance, the ship would literally be dead in the water and would have to be towed to port as there was no provision in the design to flash up either of the boilers. A Liberty ship would burn 24 barrels of oil per day while in port and 240 per day while at sea. On the Brown, this flash-up problem is circumvented by having an onboard air compressor since it would be very costly to burn fuel oil 24 hours per day. In an effort to further conserve fuel consumption, the ship uses #2 diesel fuel instead of Bunker ‘C’. By precluding the use of energy gobbling fuel pre-heaters that make Bunker ‘C’ run viscous, additional operating economies can be realized.

While in the engine room, I couldn't help but notice that only two of the three turbogenerators were on-line. When I asked about this, one of the engine room mates told be that they intentionally keep two of the units shut off. The bulk of the ships electrical power is provided by commercial diesel “gennies” fitted into their own enclosures aft of the central superstructure. By doing that, it minimizes the wear and tear of the original generators fitted on the ship. To underscore her age, the John Brown decided to drop a 2 foot length of lagging from one of her steam pipes narrowly missing one of the engine room mates. The John Brown’s crew mostly consists of Liberty ship veterans but those engine room mates take tender loving care of that steam engine. The photo at the right shows the Chief Engineer's desk and instrument panel. (Photo by Jerry Proc)

Steam is generated by two cross drum, straight tube, Babcock and Wilcox boilers at a pressure of 220 psi (450 deg F) and it is fed to a Worthington Pump and Machine Corp (Baltimore, Maryland) , triple expansion, double acting steam engine directly coupled to a single, 18 foot diameter propeller. This 140 ton engine produces 2,500 horsepower at 76 rpm and provides sufficient power to allow the vessel to sail at 10.5 knots maximum. Each turn of the screw propels the vessel 16 feet forward.

Packing my handheld VHF radio at the last moment, I too had some fun with that medium. On standby, in HAIDA’s Radio Room # 1 was John Forrest VA3XJF, a Park Class radio operator during W.W.II and Bruce Baillie VA3BBW, one of HAIDA’s volunteers. While I commented on some aspects of the ship, John elaborated on my observations. Later in the afternoon, I tried to raise HAIDA again, but with no success. Instead, another member of my local radio club , John Young VE3CRB contacted me. During the conversation, the second steam whistle demonstration commenced. Apparently he could hear the whistles coming through the radio loud and clear so I held the mike button open and broadcast the entire demonstration , including the 5-gun salute for HMCS HAIDA through our club’s radio repeater. Like the famous phrase “a Kodak moment”, this would be the equivalent of a “radio moment”.

By 16:00, after steaming in small circles on Lake Ontario for most of the day, sadly, it was time to return to the jetty. Being on the stern of the ship at that time, I was able to watch the steam operated aft winch tightening the hawsers and drawing the ship closer to the jetty with each movement of the throttle handle. It was truly a voyage into the past and is now a memory that will last a lifetime!

|

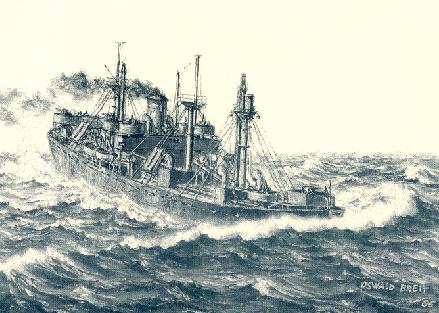

| A MEMORY: This painting by Oswald Brett is one of my favourites and is typical of how a fully laden cargo ship might ride a rough sea. Ships like these will never be seen again. |

There is additional information available about the ship on the John Brown web page. There, you can find numerous photos of her Great Lakes 2000 voyage plus additional photos featuring the work on the rivet replacement project.

|

Jan 9/22