Have you ever worked a VE0? Well, congratulations, for you have logged one of the rarest call signs in the world. But I wonder if you know what you worked? "Why, sure", you say. "It was a Canadian ship". That's true, but perhaps you'd like to know a little more about your QSO. It could have been a sleek naval ship, or the reincarnation of an eighteenth century British ship-of-the- line. It might have been a ship of science or a tough deep sea tug. Perhaps it was a schooner or the replica of a legend, created with love and care in memory of a champion of yesteryear. Each one is unique, and I'd like to tell you more about them. Care to come aboard?

Here in Nova Scotia, we're never far from the sea and I suppose we look to it much more than most people in our land. The port of Halifax has been home base to almost all the VE0 ships at one time or another. Many of the operators have been VE1's when ashore, and when at sea most of them have spent much of their time in traffic with us. So, knowing a little of the background, come along for a closer look and perhaps, smell the tang of the sea. Many times when a ham works a VE0, he thinks this is something new, but it isn't actually so. For many years, radio has been an important part of any well equipped ship, but there was little amateur operation before World War 2. It became a little more prevalent after the war, and in Canada it was the navy which carried the ball more than anyone else. The credit for the creation of the VE0 calls should go to the RCN.

Around late 1948, the Royal Canadian Navy began allowing ham operation aboard ship, using either personal or club calls. Although this privilege didn't last too long, stations did get into operation aboard HMCS Ontario, Magnificent, and Nootka. Operation was never continuous, but it resulted in the formation of the RCN Amateur Radio Society in 1951. As a result of requests by this group and other interested persons, the Department of Transport (now Industry Canada) allocated the zone figure '0' to shipboard amateur stations. The VE0N prefix was assigned to navy ships and VE0M for stations aboard government, merchant and pleasure craft.

For the navy boys, the requirements were not too difficult. An application had to be made to the Department of Transport by the senior licensed ham aboard ship and he also had to submit an application to the Captain of the ship. If the Captain agreed, he would forward it through official channels to Naval Headquarters. If the application was approved, a VE0N call was assigned to the ship on behalf of HMCS (name of ship) Amateur Radio Club. The senior ham was the licence holder and was responsible for it but any qualified ham on board could operate if the Captain approved. Only the one VE0N call could be used by all hams on the ship, and the licensee paid the regular yearly licence fee. The Navy took this one step further and allowed the use of official Naval radio equipment, provided it complied with regular amateur rules of operation.

I've digressed too much... Let's get back to the story. After the VE0 calls came into being, the first officially licensed station was VE0NA in 1954, aboard HMCS Iroquois. Aside from this distinction, the Iroquois was one of the most famous ships in the navy. From her completion in 1942, she was always in the thick of things, sinking or assisting in the sinking of fifteen enemy ships and the damage of others as well as tours of duty on the famous Murmansk run. To wind up her career of honour, she escorted Crown Prince Olaf of Norway when he returned to Oslo from exile.

After the war, she went through alternate periods of active and reserve duty, including three tours in Korean waters, returning home in 1955. In November of 1957, she was retired in Halifax, then re-commissioned and remained on the high seas until October 1962. This was the end of her active service life, and after several years of retirement, she finally went the way of all ships, no matter how distinguished. Just after the assignment of VE0NA to the Iroquois in 1954, HMCS Algonquin came on as VE0NB (the first of several ships to eventually hold this call). On the West coast, VE0NC was assigned to HMCS St. Stephen. All these ships operate fairly regularly on the ham bands but the biggest effort came in 1956 when VE0ND was allocated to the aircraft carrier HMCS Magnificent. The "Maggie" was involved in transporting troops to the Middle East during the Egyptian crisis, and a steady flow of traffic passed between the ship and the East coast on each passage between the home port and the eastern Mediterranean. Probably more than any other event, Maggie's trips pointed out the morale of amateur radio and tightened the bonds of co-operation between the Navy and the hams back home.

In 1957, the Maggie left our service and HMCS Bonaventure took over her job. With the call sign VE0NE, the Bonnie has become one of the most active of all the Navy ships as far as ham radio is concerned. No one knows exactly how many phone patches and pieces of traffic have been passed back and forth between her crew and their families but it must run into the thousands. Besides the Bonnie, quite a few others are licensed at the present time - VE0NB, the Gatineau; VE0NC, the Columbia; VE0NG, the Kootenay; VE0NI, the St. Laurent; VE0NM, the Cape Scott; VE0NU, the Terra Nova and VE0NP, the Margaree. Over the years, operation on the navy ships has run hot and cold, but one of the most extensive uses of ham radio was during the Easter Island medical expedition of 1964- 65. The Cape Scott was the transportation ship, and VE0NM ran dozens of patches back to Halifax, especially over the Christmas season. VE1LZ and VE1AGH were the fellows on this end. In addition, VE3DGX set up a station on the island and operated as CE0AG, not only giving the island it's only real communication with the outside world, but also putting a new country on the air. This whole operation was a real credit to ham radio, and the Cape Scott has been in continuous operation ever since.

Since the VE0N 'boys' use Navy equipment, they have always been able to put out pretty good signals. Top quality apparatus is forever an asset, but more so, when trying to keep phone patch and traffic schedules for weeks at a time. During the 1965-66 goodwill cruise to South America, ham radio operation was continuous, sometimes with two or three stations here in Halifax working together to handle the volume of traffic. One evening sticks in my mind particularly, as two ships cruised along side by side off the coast of Uruguay and ran hour after hour of phone patches into Nova Scotia.

VE0 calls are all issued on a club basis and in the order of request.

No ship has any permanent call and if operation is not maintained, the

call is simply passed on to another ship. With morale being the prime consideration,

most operating time is devoted to traffic and very little to rag-chewing.

This is frustrating to a lot of people, especially since the VE0 call is

quite rare, but despite their problems, the boys have always managed to

make up QSL cards and have tried to answer all of the cards received. Like

call signs, the operators change often, so perhaps some have gone astray.

If you have even one such QSL, be content, for it's almost rare as any

QSL can be. Ham radio is now firmly established in the Navy, so keep listening

and you will come across them. Please, though, a word of caution - remember

they are on the air for purposes of traffic handling. Until their schedules

are finished and they declare themselves open for general contacts, be

the type of gentlemen that every amateur should be - don't break in! Your

co-operation will be appreciated.

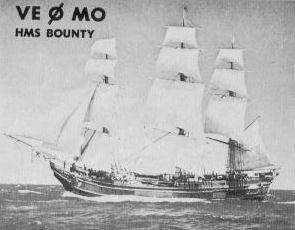

Thus we see the Navy's story of VE0, but what of the other ships.

Let's go back in history to the British Navy of the eighteenth century

and one of the most famous ships of all time - HMS Bounty; the ship of

Captain Bligh; the subject of the one of the great classic stories of the

sea. When MGM studios decided to make a movie of this story, they needed

a ship and here in Nova Scotia we build pretty good ones. In Lunenburg,

in 1960, a new bounty was built, launched and fitted out with eighteenth

century regalia and twentieth century equipment - including ham radio.

With a KWM-1 and a long wire, Spud Roscoe set up VE0M0 and made many an

operator happy with a QSO and later, a QSL that was a thing of beauty.

The Bounty travelled the South Seas and many ports of North America, finally

coming to rest as an exhibit in the waters of Tampa Bay, Flordia.

The Canadian Scientific Ships Baffin and Hudson, VE0MJ and VE0MX are the pride of the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, one of the best scientific centers in Canada and a world leader in ocean research. These ships look more like luxury yachts or small cruise ships, but inside they are crammed with laboratories and the latest devices for unlocking the oceans secrets. Their work takes them from the tropics to the Arctic and they are quite active on the ham bands. 80 and 20 meters are preferred with more CW than phone. They handle some traffic, but not as much as navy ships, so the chances of a casual QSO are much better. Be on the lookout for them and when your QSL arrives, you will have a souvenir of one of the most technologically advanced ships afloat.

There are several other VE0M stations which are sporadically active - VE0MH and VE0MI on the icebreakers Sir William Alexander and N.B. McLean; VE0MP on the Royal Canadian Mounted Police cutter "Wood" operated by VE1RX; VE0MS, the ice breaker D'Iberville; VE0MM, a private cruiser owned by VE1ARY; and VE0MB operated by Captain Louis Romaine and the Lurcher Lightship off the south tip of Nova Scotia. This one is quite active on 75 meter phone, keeping regular schedules with friends ashore.

There is always a tale of adventure associated with any VE0 station, and any of us who have operated with them have our favourite stories and memories. My fondest thoughts are the "Foundation Vigilant", a big, brawny 'ocean eating' tug with the call VE0MK. In December 1964, the "Vig" left Halifax to cross the Atlantic with a huge, old, grain carrier in tow, bound for the scrap yards of Bremerhaven. "Mick" McWilliams was the operator and we agreed to keep schedules each morning on their way across. The trip wasn't supposed to take more than a few weeks but the rough old Atlantic had other ideas. As the days went by, the seas became higher, the winds stronger and progress slower. The casual morning chats soon became traffic as the Captain and crew began letting the folks at home know of the situation. Trouble developed with the radar and we spent hours troubleshooting it by 20 meter CW. After a day or two, the radar was fixed and then the real storms began. Day after day of towering seas and howling gales, the towing line broke. The grain carrier disappeared in the storm. Chasing after it with her radio on constant watch to warn other ships of the danger of the drifting mass of steel, the Vigilant tried to "hook up" again, but each attempt met with failure. Day after day, I met Mick on 14.022 Mcs and hoped they had met success. On each day, it was the same status - "No change, George, still gale force winds. Can you take some traffic?" I kept thinking, I wonder what thoughts would be going around all these homes if this schedule hadn't worked out? The ship was already overdue at her first port of call in England and was still only half way across the Atlantic. For eighteen days, the gales drove the Vigilant and her wallowing target back across the Atlantic, until at last a line was secured and the long, hard, pull began again. Food was almost gone, and fuel was low, so they headed for the Azores while we cleared every message we could before they docked. I 'stood by' every morning for a week and a half, and one morning signals came pounding through once again. Because of some problem with local communications, they had no success in getting messages back to Canada, so that morning there was a lot of traffic on 20 meters!

Off they headed again for England and into another succession of gales and winter storms. Christmas and New Years had come and gone and by the end of January, I had become acquainted with the families of every man aboard. There's always something very wonderful about putting this amateur radio of ours to good use. Mick and I found a lot of personal satisfaction in keeping these schedules without a hitch. Finally, in mid-February, the Vigilant reached Falmouth England. From there, she continued her voyage through the English Channel, up the Straits of Dover, the North Sea to the River Elbe and finally finishing the long voyage at Bremerhaven. Right to the last day, our schedules went through and after the hulk was turned over to the scrap yards, the Vigilant turned homeward. Misfortune struck again. As she headed down the channel, her Captain became seriously ill and she raced for the nearest port and hospital. Messages flew back and forth to Canada and his wife flew to England to be at his side.

A relief Captain also flew over and the ship headed for home with a different hand at the helm. Again the storms, but this time there was no great weight to hold her back and she was hurtled along with the wind and the waves. The message total by this time was over one hundred and fifty and every family at home knew of her day-to-day progress. On a brisk day in mid-March, she finally slipped into Halifax harbour to her home berth and the arduous voyage was over - one more story for a ship whose every voyage was an adventure.

No mention of the VE0 ships would be complete without a salute to one

which is a living legend. Back in the 1920's, one of the largest fleets

of tall schooners sailed from Lunenburg to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

After catching as many fish as they could, the schooners spread all sails

in a breakneck race for port because the fastest schooner made the most

money by getting her catch back first. Bigger and better schooners were

build in the quest for speed and performance.  One

of these was named "Bluenose". Hers was to be a career of achievement attained

by few ships, for not only was she big and caught a lot of fish, she was

fast - so fast she could show her heels to almost anything that dared try

to outsail her. It was inevitable that she be challenged to race against

her competitors and so began the famous International Schooner Races, in

which Bluenose met and defeated every candidate. She was a toast of the

town, a Province and a nation, but she was still a working ship. As the

years went by, the tall schooners gradually succumbed to the intrusion

of engines and one by one, they disappeared. Bluenose kept working, but

in the early 1940's, she struck a reef off Haiti and swiftly slipped beneath

the sea of which she was so much a part. There were black headlines and

sorrow in Nova Scotia, but she lived on in memory and for many years, there

was talk of building a replacement - someday. Finally, the Halifax firm

of Oland and Son Ltd, decided this should be done and in the summer of

1963, Bluenose 2 was launched from the shipyard which had built her famous

ancestor. In early, 1964, she made her maiden voyage from Nova Scotia to

Cocos Island where a ham station was set up under the call TI9FJ. On her

way home, her engineer became ill and was replaced by VE1AGM. He has been

with her ever since. That fall, she was assigned VE0MY and with a Collins

KWM-2 and 30L1 linear, she has become a familiar voice on the airwaves.

She spends her summers cruising the waters of North America and the winters

in the Caribbean. Hundreds of hams the world over have enjoyed a QSO with

her. Everywhere she goes, she carries the pride of Nova Scotia - black

hull, white sails and golden spars shining in the sunlight. She is the

embodiment of grace and beauty.

One

of these was named "Bluenose". Hers was to be a career of achievement attained

by few ships, for not only was she big and caught a lot of fish, she was

fast - so fast she could show her heels to almost anything that dared try

to outsail her. It was inevitable that she be challenged to race against

her competitors and so began the famous International Schooner Races, in

which Bluenose met and defeated every candidate. She was a toast of the

town, a Province and a nation, but she was still a working ship. As the

years went by, the tall schooners gradually succumbed to the intrusion

of engines and one by one, they disappeared. Bluenose kept working, but

in the early 1940's, she struck a reef off Haiti and swiftly slipped beneath

the sea of which she was so much a part. There were black headlines and

sorrow in Nova Scotia, but she lived on in memory and for many years, there

was talk of building a replacement - someday. Finally, the Halifax firm

of Oland and Son Ltd, decided this should be done and in the summer of

1963, Bluenose 2 was launched from the shipyard which had built her famous

ancestor. In early, 1964, she made her maiden voyage from Nova Scotia to

Cocos Island where a ham station was set up under the call TI9FJ. On her

way home, her engineer became ill and was replaced by VE1AGM. He has been

with her ever since. That fall, she was assigned VE0MY and with a Collins

KWM-2 and 30L1 linear, she has become a familiar voice on the airwaves.

She spends her summers cruising the waters of North America and the winters

in the Caribbean. Hundreds of hams the world over have enjoyed a QSO with

her. Everywhere she goes, she carries the pride of Nova Scotia - black

hull, white sails and golden spars shining in the sunlight. She is the

embodiment of grace and beauty.

This is, in an very brief way, something of the story of the VE0 ships.

To anyone who loves ships and the sea, or has ever had the old dream of

sailing away to far horizons, I hope it's been a little insight to the

men and ships who put these calls on the air. For their help and co-operation,

I'd like to thank the people from Foundation Maritime Limited, the Bedford

Institute of Oceanography, the Navy's Atlantic Region Information Office,

Orland and Son Limited, R.W. McWilliams and VE1AGH, VE1AKO, VE1AX, VE1FQ,

VE1LZ, VE1PW and VE1PX. With their help and the memories of many hours

in front of my own receiver, I've tried to take you aboard for just a few

minutes. I hope it's been enjoyable.

.....VE1TG