by Jim Thoreson

Webmaster's intro: Robert Peary (May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer who claimed to have been the first person, on April 6, 1909, to reach the geographic North Pole. Peary made several attempts to reach the North Pole between 1898 and 1905. For his final assault on the pole, he and 23 men set off from New York City aboard the Roosevelt under the command of Captain Robert Bartlett on July 6, 1908. They wintered near Cape Sheridan on Ellesmere Island and from there departed for the pole on March 1, 1909. The last support party turned back on April 1, 1909 at latitude 87°47' N. On the final stage of the journey to the North Pole only five of his men, Matthew Henson, Ootah, Egigingwah, Seegloo and Ooqueah, remained. On April 6, he established Camp Jesup near the pole. In his diary for April 7 (but actually written up much later when preparing his journals for publication), Peary wrote "The Pole at last!!! The prize of 3 centuries, my dream and ambition for 23 years. Mine at last..."

~~~~~~~~~

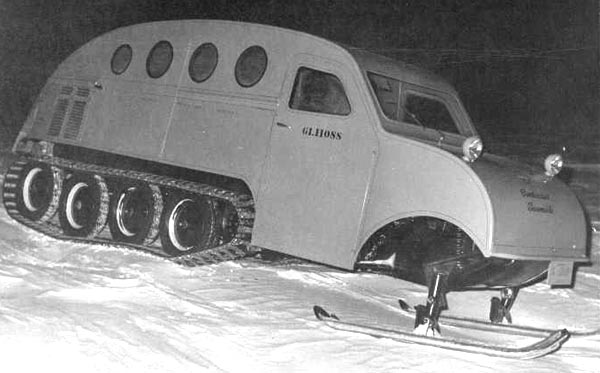

While I was stationed in Alert, someone got the bright idea to follow Admiral Peary's track as he ventured to the North Pole in 1909. A number of us got together and departed Alert in a pair of Bombardier B12 all-terrain vehicles. The group of 8 included Alert's CO, which I believe was RC Sigs Major Berry at the time, Taffy Baynam and myself representing the RCAF, Navy hands, Sigs types to represent all three services as well as the Officer in Charge of DOT Aeroradio.

Our group continued to Markham Inlet where one B-12 remained while the

other continued on to Cape Sheridan, the starting point of Peary's expedition.

We headed north along the coast and eventually came upon remains of Admiral

Peary's camps. There were numerous fuel cans, hard tack, wooden boxes,

and broken sled runners.On the return trip, several artifacts were retrieved

and taken back to Alert where they were put on display. As far as I know

they might still be on display. I can't remember the duration of the trip

because of the 24 our daylight but I do know that it was extremely

rough bouncing all day in those snow machines.

|

| #NT1 - The members of Northern Trek. Some of Peary's "cache" is visible in the upper left corner of the picture. See photo NT-5 for more detail. (Photo by Jim Thoreson) |

|

| NT#2 - Time to refuel the B12's. Note the date of 3/60 on the fuel drum. (Photo by Jim Thoreson) |

|

| NT#3 - Hey! We're supposed to go that way. (Photo by Jim Thoreson) |

|

| NT#4 - The Bombardier B12 in its native realm. (Photo by Jim Thoreson) |

|

| NT#5 - Markham Inlet. The Arctic has a beauty all of its own. (Photo by Jim Thoreson) |

|

| NT#6 - The first signs of Admiral Peary's expedition. (Photo by Jim Thoreson) |

|

| NT#7 - More evidence from the expedition. (Photo source unknown) |

|

| NT#8 - Some of the artifacts were retrieved and brought back to Alert. (Photo source unknown) |

|

| NT#9 - Sign post. This signpost was put up by someone

at the point of land at Cape Sheridan

where the pole trekers leave land and strike off across the ice pack for the pole. (Photo source unknown) |

KITE FLYING IN ALERT

By Jim Thoreson

Our shift was really bored on a set of "days off" in the summer months

so we decided that since there was so much wind up at Alert, we should

build a large kite. Our group managed to built one about seven feet high.

It was the old style kite with a long tail on it. Once finished, we got

a couple of balls of twine from stores and away we went.

Our shift was really bored on a set of "days off" in the summer months

so we decided that since there was so much wind up at Alert, we should

build a large kite. Our group managed to built one about seven feet high.

It was the old style kite with a long tail on it. Once finished, we got

a couple of balls of twine from stores and away we went.

There was about four or five of us there. We got the kite airborne and away it went. We kept paying out the twine until one ball was all used up. We tied on the second ball and continued. By this time, the kite could barely be seen high over the pack ice. As the second ball of twine was paid out, the man holding the string missed the end as it slipped through his fingers. By the time he yelled, it slipped through the rest of our hands as well. So the kite was off on it's own.

The weight of the twine kept it flying and upright to a certain degree, but in any case, it dragged the twine along the ground and the kite continued its flight due north, out over the ocean. Since it was summer, there was a small piece of water between the pack ice and the shoreline. As the kite continued its northerly route, the twine hit this stretch of water which created additional drag and caused the kite to gain altitude. As the wet string left the water and slid over the ice pack, it picked up snow which started to coat the twine. This too created more drag, causing the kite to continue rising. Soon it was out of sight, still travelling north and at a high altitude. It was never seen again. In retrospect, we were sorry we didn't put a bunch of tinfoil on it, and maybe it would have caused the Russians to scramble their jets if spotted on their radar.

AERIAL ADVENTURES IN THE HIGH ARCTIC

by Maurice Drew

I don't recall the date but it was 1965 and we were on our way to Edmonton via Resolute when a bad storm came up. Our flight could not land at any of the alternates, including Thule and it didn't have sufficient fuel to return to Edmonton. I'm sure F/L Nurse was the pilot. I was in the cockpit jump seat when he declared an emergency. Although Thule was closed it was the only field with ground control radar. I was in my early twenties and remember it being an adventure. What I didn't know until we were safely on the ground and a few miles from the terminal in a howling gale was that we actually landed without the gear down! When we made it to the mess in the early morning, as in about 2 AM, I started to shake uncontrollably. The USAF cook gave me a glass of orange juice laced with sugar. I guess he knew how to treat diabetic shock, even though I am not diabetic. It worked!

Another time we lost our rear elevator trim on our way into Resolute in a Herc. I think I hold a record for being stranded in various places throughout the Arctic. We were returning form Alert and an International Geophysical Science excursion into the Canadian Arctic. Many of the scientists, a few from the Defence Research Board here in Ottawa, had their delicate instruments in cardboard boxes and canvas sacks. The RCMP officer at Resolute Bay decided to kick each of them to be sure there was no contraband (such as liquor from Thule). There was hell to pay for the damage and the kerfuffle caused a two day delay in getting the flight back on schedule! I often wonder what happened to the RCMP officer. He was the same man who drove me to visit the Indian village a few miles west of the military base and left me there to walk back!

Also, I have a photo slide somewhere of a ship caught in the ice at Thule. The ship contained several months' supply of booze, cigarettes and other goods that were too tempting for some to just leave there. So the US military brought out a gun and blew the ship to pieces!

A TENSE SITUATION IN THULE

by Gord Walker

Our flight originated in Edmonton and already had some civilian carpenters and labourers onboard when it stopped in Inuvik to pick up about a half dozen of us Navy types. It was August and passengers on the Herc flights at that time of year were secondary to the cargo and supplies heading north. In our case the load was roof trusses which were lashed down in the centre of the hold while the passengers were seated along the sides of the fuselage facing inward. As we boarded, the cargomaster , a seasoned RCAF Master Corporal, told us that the roof trusses were an awkward load that could shift despite their being lashed down and instructed us to keep our feet braced solidly against the trusses throughout the flight. It was especially important during take-offs and landings, so they wouldn't shift and crush us against the fuselage. At the time it seemed like a valid request, but in hindsight I think it was the cargomaster's little joke on the naive passengers.

Our Herc was one of two that left Edmonton enroute to Alert, the second carrying only crew and supplies. Both were scheduled to stop overnight in Thule before making the final leg of the journey to Alert, and both were to reach Thule within minutes of each other, just in time for dinner.

The other Herc landed first and we came in only minutes behind, but

rather than getting a warm American welcome we were met with jeeps and

a personnel carrier carrying a platoon of armed Marines, rifles at the

ready. They stormed onboard the aircraft and ordered everyone, including

the pilot and crew, to get out and stand beside the plane facing it, arms

outstretched over our heads and hands resting against the side of the fuselage.

Apparently there had been a mix-up in landing clearances and only one Herc

was expected, hence the panic when a second one arrived onscene.

It had become quite warm and stuffy inside the Herc and most

of us had stripped off our jackets and were dressed only in bells and gunshirts

when ordered off the plane. It was quite chilly despite it being

August and we were kept alongside the plane for about 45 minutes, although

the Marines did permit us to stand at ease after the first 15 minutes or

so, but still facing the aircraft. They still kept their rifles trained

on us too.

Finally the paperwork got straightened out and we were permitted to

get what we needed off the plane and directed to our quarters for the night.

Of course by now the kitchen was closed so we had to make do without supper,

at least one that consisted of food. The flight to Alert the next

morning was a bit rough, or seemed to be, and the noise inside the aircraft

certainly did nothing to help the headaches which many of us were sporting

as a result of the previous evening's "socializing" with our American friends

in Thule.

MAD MAX OF THE HIGH ARCTIC

by Maurice Drew.

I knew a pilot who set up a race among Herc's C01, C02 and C03 during Operation Boxtop in Alert, circa 1964. The prize was bragging rights. The pilot's name was Max, for Maxwell. I don't know who the other three were. but he also went by the nickname "The Silver Fox" because his hair was bright white. One day, he nailed a red flag on the corner of the generating shack next to the runway and challenged other pilots to knock it off during a fly-by. During a race he would fly just a few feet above the ground, gear up, with the tailgate open while the crew yanked on a chain releasing the oil drums. The drums bounced around the runway and created a mess for the ground crew to mop up Just imagine if anyone had been hit by a flying oil drum! On one of these races he was in such a hurry that when he arrived Thule and approached a hanger, he rotated too late and knocked the tip off a wing. He was grounded, of course but he was a hell of a pilot.

It was Max at the controls one afternoon while I was aboard his Herc destined for Thule. I was the only passenger and except for the crew, the plane was empty. I was in the cockpit when he asked me if I had ever been to the Pole. He cut the outboard engines and we flew just above ground level. I presume he knew how to find the Pole, a mere 400 miles north of us. In returning south we buzzed a herd of muskoxen. When we got above the Lincoln Sea he re-started the outboard engines and climbed at a rate that glued me to the seat. I was young and confess to having enjoyed the thrill. But in retrospect the guy was cavalier, to say the least, with others' lives.

Max, and others, used to fly into Alert after the Air Force installed GCA (ground radar) by skirting the glacier between Mr. Pullen and Chrystal Mountain. They're not real mountains, just hills. The radar couldn't see the Herc through the terrain. He would roar through the gap and moments later buzz the GCA shack and scare the living daylights out of the radar operators. This was a common occurrence in the early sixties. It was this kind of by-the-seat-of-your-pants flying that caused the C-130 crash in October 1991 and the subject of an amazing book called Death and Deliverance.