Acting Lieutenant-Commander R.P. Welland, D.S.C., R.C.N.

19 December, 1944 to 2 September, 1945

![]()

by Bob Welland

Acting Lieutenant-Commander R.P. Welland, D.S.C., R.C.N.

19 December, 1944 to 2 September, 1945

![]()

by Bob Welland

December 19th, 1944 was a good day. "She's yours", said Captain Harry DeWolf. I was now the captain of HMCS HAIDA. Harry DeWolf had been her captain from the day she was commissioned in 1943 and with his crew had made her into one of Canada's famous warships. HAIDA took a leading part in close encounter, night-fighting against the Germans that ultimately decided which Navy controlled the English Channel.DeWolf, nicknamed "Hard-over Harry" because of his spectacular ship-handling, had been promoted to captain's rank and I had been chosen to succeed him. Whether he had any say in that is unknown to me, but I served with him in the destroyer ST. LAURENT in 1940. Those were the days of the Dunkirk evacuations of the British army, the desperate time when we were losing the war. So we knew one another in the way a junior lieutenant knows his captain. "Good luck", he said.

I was still a Lieutenant but had the rank of Acting Lieutenant Commander which had been bestowed on me a year before when I had been made the captain of HMCS ASSINIBOINE. My mother wrote me a letter at the time, "Bobby, aren't you a bit young at 25 to be a destroyer captain?" I wrote back saying, "Aren't you a bit young at 39 to be my mother?" Mother never got beyond 39 until she passed away at age 100!

Whether I was too young never occurred to me. By that time, I had been in the navy seven years. My career started when, as an 18 year-old officer-cadet, I was sent to England to train with the Royal Navy as Canada had no training ships. When war broke out in September 1939, I had been at sea for three years starting at the bottom of the pyramid as a cadet on board a British warship. That was below the status of an Able Seaman. In a year, I graduated to a midshipman and after two years at sea, I became a Sub-Lieutenant and was for the first time judged to be an officer.

For those three years, I slept in a hammock and pushed a wire brush up ten-foot long boiler-tubes; learned about anchors and cables and how to handle them on a stormy night; could read Morse code at 30 words a minute along with flashing light; became familiar on how to operate the evaporators to make the ocean's salty water fit to drink; handled boats with 40 foot pinnacles that carried a 100 men and three-engine 30 knoters with machine guns in the bow. In addition, I had been part of the crew in a 6 inch gun turret that hurled shells some 12 miles; sailed a 27-foot whaler around the Island of Tobago, while sleeping on the beaches; navigated a 10,000 ton cruiser from Aden to the Seychelles Islands and on to Singapore using my own sextant on the sun and stars (the ships navigator checked my work). An Oxford don (doing his reserve time) criticized my journal for poor English, tedious phrasing and more. In short, I knew a good deal about operating a high powered warship; I knew the rules to duck hurricanes and danced with the taxi girls in Penang.

On September 3rd 1939, I was a 21 year-old Sub-Lieutenant on board a Royal Navy destroyer, HMS FAME, when the British Prime Minister, announced over the radio, "We are at war with Germany".

I was delighted that I was prepared for this moment. It meant that I would have a chance to do what I had been training for all these years . I was not in the least upset - quite the contrary; the Germans had been threatening for years. Now they were in Poland, and England was also on their list/ It was past time to take a stand."I was in FAME for the first eight months of the war fighting against the German U-boats that were busy sinking merchantmen around Britain. We fought along the Norwegian coast to prevent its invasion but lost that one. I was introduced to attack by Heinkel and Junkers bombers and having torpedoes run close by. One memorable event was the time when our destroyer flotilla of eight ships met the first convoy of Canadian soldiers being transported to England; five great liners carried 8,000 of them. My captain passed close by each ship and we gave them three cheers as loud as 125 of us on board could shout. That was in late December 1939.

I was transferred from the British destroyer FAME to the Canadian destroyer ST. LAURENT in March 1940. By June, we were off the French coast rescuing British soldiers who had been defeated by the Germans and chased to the coast. Harry Dewolf was our captain at the time. We saved quite a few soldiers at a place called St. Valery-en-Caux and but were attacked by Heinkels and German artillery when our boats went inshore to pick up the soldiers. In July of that year, ST. LAURENT made one of the greatest rescues of the war. We picked up 863 oil soaked survivors of the liner ARANDORA STAR and landed them in Glasgow 30 hours later. About the same number were left behind but they had all died. It was extremely crowded on board our destroyer as there were nearly a thousand people aboard including the crew of 130. DeWolf told us to put the dead out of sight of the living- he paid attention to details like that. In those days the Germans were victorious everywhere.

In 1941, I started to specialize in Anti-Submarine Warfare. I did that because I knew I was a natural at hunting down submarines and would have more opportunity if I had the magic letters A/S after my name. That was a major blunder. When I qualified, I was not sent back to sea. Instead, I was ordered to train officers and sailors in Canada. Over the next year, in 1942, I gave, at-sea, submarine-hunting training to A/S operators of dozens of corvettes, minesweepers and Fairmile launches all equipped with the magic ASDIC detection equipment. The hidden benefit for me turned out in getting to know a host of RCNVR/RNR officers and men, the people who did most of Canada's wartime seagoing. I'm still enjoying their company in our many naval organizations.

In March 1943, I was again at sea. This time as the Executive Officer of the destroyer HMCS ASSINIBOINE. My captain was Commander Ken Adams, a highly skilled seaman, who was also the commander of our Escort Group. We shepherded many convoys across the Atlantic - 50 to 80 merchant ships loaded with the means of winning the war in Europe. Our Group usually had two destroyers and eight corvettes. We picked up the convoy off Newfoundland and escorted it 2,000 miles into the Irish Sea. Then we took another convoy back and repeated this - storing and fuelling at each end of the run which was St. John's to Londonderry. We fended off U-boats and Focke Wulf bombers; we picked up survivors of torpedoed ships; we got over 90 percent of the merchantmen safely across the Atlantic. Exhausting? - yes. I became ASSINIBOINE'S captain in September 1943 because my captain became ill. That's when my mother wrote to me.

A year later, I was still the captain. We operated along the French coast in support of the Invasion of Europe; we had changed roles with the Germans; now we were winning and hunting them down. Allied destroyers operated right in-shore blockading their routes and harbours; we were wary of glider bombs, shore batteries, and U-boat efforts to drive us off. We had taken the fight to Germans.

These were the types of operations that allowed me to speak into the voice-pipe to my coxswain in his armoured cubicle, one deck down from the open bridge: 360 revs, hold the course, and feel the acceleration as 36,000 horsepower kicked in, then to order, "open fire" and be shaken up as the 4.7 inch guns blasted off, with the next salvo only seconds behind. One night, we set a French field of hay on fire while shooting up a German convoy. That was in Audierne Bay - now a tourist resort. Behind my back, the sailors nicknamed me "Rapid Robert" !

It was during these operations that I was ordered back to Canada to take command of HAIDA. I flew back in a converted Lancaster bomber - 15 hours non-stop to Montreal. It was much superior to that of wallowing around in a ship for 5 days. HAIDA had been just been overhauled and was almost ready to sail when I joined her in Halifax. The Executive officer was Lieutenant Ray Phillips. He had been on board since she commissioned a year earlier and was a veteran of the wild actions that had made the ship and Harry DeWolf notable; so notable that when HAIDA left Portsmouth to return to Canada all the Royal Navy ships in the harbour got their crews on deck and gave her three cheers. DeWolf's HAIDA received a gold medal for shooting up German destroyers and the RN were generous in their praise.

Ray Phillips knew the ship, as did many of the crew. He was 22 and had been at sea since 18, all of it during the war. I never asked if his mother thought he was a bit young to be second in command of a 36 knot, 8 gun warship, with 240 crew. On our return to England on December 26, 1944, we sailed alone. I put HAIDA on a southern route near the Azores where the weather was better and arrived in Porstmouth four days later. During the voyage I got to know her much better; she didn't flex with the seas in heavy weather as much as my previous three destroyers. This was most comforting. In contrast, ASSINIBOINE would blow the siren if the wire from the bridge to the funnel was even a bit tight! HAIDA had superior acceleration. With all three boilers on-line, she forged ahead. The stokers were not afraid to push her - to open all sprayers, speed up injection pumps and spin the throttles open. Acceleration had become important. The best solution against a German homing torpedo was to outrun it - full speed ahead!

I was ordered to Scapa Flow to join a British destroyer force engaged in assaulting the Germans in Norway. Our Canadian destroyers IROQUOIS and HURON and now HAIDA were part of the force as was our aircraft carrier PUNCHER. My past captain from ASSINIBOINE, Ken Adams, was now the captain of IROQUOIS ; a friend, Harold Groos, was captain of HURON; Captain Roger Bidwell was CO of PUNCHER. We had an impressive collection of new Canadian ships ready for action. The operations that followed were intense as far as the flyers were concerned. Their strikes were successful but the German navy chose not to challenge us in the open ocean. We were indeed winning the war!

My final operation of the war was a memorable one. I was ordered to take HAIDA to Greenock, Scotland to prepare for a special task related to an upcoming Arctic convoy. In two days we were fitted out with a system to refuel motor launches. These boats were 110 footers , diesel engined, and manned by Russians. HAIDA's job was to escort them to Murmansk, Their crews, all reservists, were high on enthusiasm but low on skill. At the end of 24 hours, I had lost three in the Hebrides Islands. My navigator, Gordie Welch, an RCNVR stock broker from Toronto, said, "By extrapolation, we'll lose the last one 1,200 miles short of Murmansk" . Ray Phillips said, "Maybe they don't want to go to Mother Russia". But the situation soon improved. I anchored in the Faeroe Islands to have a "get-together" and have our engineers coach theirs. All the boats had tied up alongside HAIDA. It was the best party of my war; we and the Russians sang, ate and drank for a whole day. We learned a thing or two on how to party - their entertaining abilities outshone ours ten to one - one Russian sang the song Pinafore in English while others did Cossack dances! Ten days later, all sixteen boats motored into Kola Inlet proudly flying the Soviet ensign.

The German U-boat fleet fought hard until the very end. When we sailed from Russia to escort convoy RA 66 to Scotland, we knew from Intelligence that over twenty U-boats were waiting off Kola Inlet to attack. This happened to be the very last convoy of the war. There were 26 ships and indeed we were attacked. The U-boats failed to sink any of our convoy and our strong escort sank two U-boats. German records tell that U-427, commanded by 26 year old Lieutenant Gudenus, fired two torpedoes at HAIDA but missed; they also record U-427 being savagely attacked. The son of that U-boat captain and I discovered each other through the HAIDA web site. His name is Stefan. Stefan, not yet conceived when his dad had us lined up in his periscope, has thanked me for making an unsuccessful depth charge attack. I have thanked him for his father's inaccurate torpedo aiming!

Victory in Europe was declared on 8 May 1945 - the war was finally over! I looked forward to hurrying back to Canada to revisit my wife and baby son but that was not to be. "Proceed to Trondheim" said the sailing order. The Canadian and Norwegian government (in exile) wanted a Canadian presence in the liberation celebrations as "Little Norway" in Toronto was an important wartime organization in Canada. Norway had been under German occupation for over five years. HURON and HAIDA eased into Trondheim harbour (escorted by a German minesweeper through their minefield) a few days after the war ended. Hundreds of Tronheimers swarmed aboard our anchored ships. Our sailors gave away the canteen stores, chocolates, cigarettes - all of us got kissed. At a town hall ceremony, the Mayor had a pretty girl teach the two ship captains, on stage, how to make a toast. "Ein skol- dien skol- alavaka alles skol" and then bottoms-up, the aqua vite. It took her four attempts before we got it right!

We accepted the surrender of some German establishments as there were still 84,000 troops in the area. We sent our unarmed 300 libertymen ashore to mix with the locals. They were advised not to pick fights at odds of 84,000 to 300! A lot of tears were shed that week especially Norwegians ones for joy!

I stayed in the Navy after the war, although my wife Stephanie and I kicked around the idea of becoming civilians. I was given good jobs during my career. The first was that of the Executive Officer of the Royal Roads Naval College, in Victoria - for two years; then on a ship design staff (the ST. LAURENT class) in Ottawa; then to the Staff Course in Greenich, England, for a year. We certainly moved a lot during that period.

In 1950, five years after WW 2 ended, the Korean war flared up. I was into another war - now the captain of a new destroyer, HMCS ATHABASKAN 219. By this time, Stephanie and I had three small boys. A few months after being given command of this fine new ship, we sailed for Korea. The war will be over in a few months predicted the "wise men" and news forecasters. Eleven months later, I guided ATHABASKAN back into Esquimalt harbour. Stephanie was on the dock holding our four month old daughter - my first sight of her. I had been away so long my three little boys were not sure who I was and who was that strange man kissing their mother?

My Korean war was quite different - no U-boats, no convoys, no icing up but enemy shore batteries and mines in river estuaries were the real hazards. We saved many refugees lost at sea in open boats; we fed lighthouse keepers marooned on remote islands; we armed and trained islanders to defend themselves. On one occasion, I held fire so several hundred enemy civilians who were building gun emplacements could escape before we blew up their handywork. No one was killed. Our doctor, Bruce Ramsay, operated on a dozen wounded civilians on my dining room table. These were brought out to our ship by local fishermen. Bruce trained our electrical engineer, Bob Grosskurth, to be his anaethetist. We had a six year old girl on board for two weeks. She been shot through the chest by an aircraft round. Her mother stayed on board and helped our cooks. Happily, the child left the ship rosy cheeked.

ATHABASKAN took a leading part in the run-up to the successful Inchon landings; we went up the river to Chinnampo to help save the American Army. The President of South Korea gave ATHABASKAN a special citation. We were the first ship of the entire United Nations force to land an assault team in enemy held territory. Lieut. Cdr. Stewart Peacock had led the party. I've since donated the (illuminated) citation to the Chief and POs mess in Esquimalt. A Korean lieutenant and his signalman lived with us for the entire period; we learned about his country from this clever and observant team. On an occasion when I was about to fire on an inshore target (Kunsan), Kim said his family summer home was on the beach close by. There were other targets. The Korean people, both North and South, were mystified as to how it was possible for a bunch of foreigners (United Nations) to arbitrarily split their country and divide families who had lived in their land for 3,000 years of recorded history. So was I and so was Kim and his signalman.

I served in the Navy for another 12 years. In the rank of Captain, I commanded the new officer training establishment HMCS VENTURE in Esquimalt, a facility which is still operating. Also, I commanded HMCS ONTARIO, an 11,000 ton cruiser and took her on extensive tours to the Far East and elsewhere. For three years I commanded HMCS SHEARWATER, the Navy's great naval air-arm base near Halifax. We operated over 100 naval aircraft. Nearby, we berthed the carrier HMCS Bonaventure at our 1,000 foot wharf when she wasn't at sea. We were the only airport near Halifax so we hosted four airlines, notably Trans Canada. Our sport teams were a constant threat to the rest of the Navy along with the Army and Air Force. We enjoyed engaging the Nova Scotian universities: Dalhousie, St. Mary's, St. Francis Xavier, Acadia but we didn't always win. Amongst the 1,100 kids in our local public school, four of them were ours.

In 1960, I was promoted to Commodore and spent two years in Ottawa, mainly in conceiving a new ship class - namely the 280 and introducing big helicopters into the destroyers. I was deeply involved with the Defence Research Board and advances in sonar and the hydrofoil project. The Cold War was running hot for Ottawa desk commanders.

In October 1962 I was yanked out of Ottawa and made the sea-going commander of the fleet (CANCOMFLT) just prior to the Cuban missile crisis. I joined HMCS BONAVENTURE and remained in her for the next two years. During that period she had two captains. The first was Freddy Frewer who had been a junior watchkeeper in ST. LAURENT in 1940. Fred was probably the most widely known officer in the Navy. He was a natural athlete, played sports better that most and was adept in hockey, baseball, football and squash. On our championship teams, Fred was often the only officer. The sailors knew him as "Frew". He also had the reputation as one of the Navy's sharpest wits. Fred was succeeded by Bob Timbrell.

Timbrell and I had worked closely together from 1947 when we took a leading part in the design of the ST. LAURENT class destroyers also known as the "Cadillacs". We were both specialist anti-submarine officers and a few years later our new destroyers had four sonar sets and one gun, instead of what had been the previous standard - one sonar and four guns! I served for two years as CANCOMFLT, almost all it in BONAVDNTURE. On one training exercise I had command of 41 operational ships and four squadrons of aircraft. One of those ships was HAIDA, still operational, but nearing the end of her service life but still faster than some of the new ones!

During that period and for years later, our Navy had the reputation in NATO of being at the pinnacle of capability in hunting down submarines - both our own for practice and those of the Soviet navy. This period was also the height of the Cold War. Soviet, nuclear armed submarines routinely prowled within missile range of our Canadian cities. We knew how to find and sink them and were ready to do so. Soviet bombers tested our airspace. The "Diefenbunker", a nuclear survival facility for the Government of Canada, was built in Carp Ontario, just outside of Ottawa. Kids were taught to hide under their school desks in case of a nuclear attack! Our ships were at sea and aircraft on the flight decks; it was a busy time for me and I was doing what I had trained for since I was 18.

In August 1964 I was promoted to Rear Admiral and appointed Vice-Chief of the Navy at age 44. My seagoing days were over so I retired two years later and entered the business world.

My children find it amusing that I still have a crumpled sheet of paper on which I wrote that I intended to become the captain of a warship, and an admiral, and to make a million dollars. The date on the paper is 1932. I was just 14, lived in McCreary, Manitoba and had never seen salt water! I now live in Surrey, British Columbia.

Bob Welland, 2008

PHOTOS

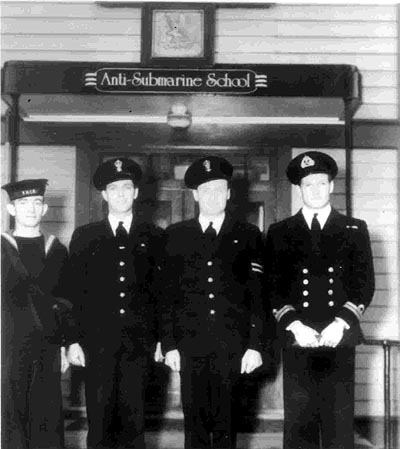

|

| 1942: Four anti-submarine specialists were sent to the West Coast (HMCS NADEN) in January 1942 to establish a new anti-submarine training school. By the end of three months, there were 400 students under instruction by some 20 staff, preparing recruits to operate on-board ASDIC equipment. Bob Welland is at the right side. |

|

| Robert Welland as seen while he was HAIDA's Commanding Officer. |

|

| Stephanie Welland in 1945. |

|

|

|

| Captain Fred Frewer | Ray Phillips | HMCS BONAVENTURE recovering aircraft. |

| All photos in this document are from the collection of Bob Welland. | ||

OBIT

WELLAND, Robert Philip Rear Admiral, RCNDied May 28, 2010, in White Rock, B.C., after a brief illness. Born in Oxbow, Saskatchewan, March 7, 1918. Father of Michael, Tony, Christopher and Gill (Christauria). Stephanie their mother, predeceased him, as did his companion of many years, Margot Hanington. He is survived by two sisters, Greta (Mrs. Allan Torrie) and Pamela (Mrs. Alan Abercrombie), his grandchildren, his sister-in-law Helma Campbell, and by many nieces, nephews and step-children.

He grew up in McCreary and Dauphin, Manitoba. He joined the Navy at age 18 as an officer cadet and spent the next 4 years at sea with the British Navy. In 1940 he joined the destroyer, HMCS St Laurent participating in the evacuations from Dunkerque. Always in destroyers during World War II he became captain of HMCS Assiniboine at age 25, and was captain of HMCS Haida for the last year of the war. He commanded the destroyer HMCS Athabaskan in Korea for the first year of that war. In peacetime he commanded the cruiser HMCS Ontario, the Naval Air Station, HMCS Shearwater, founded the Officer training establishment HMCS Venture and commanded the Canadian sea-going fleet during the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962 from the aircraft carrier, HMCS Bonaventure. He became a specialist in anti-submarine warfare during World War II and was active in the development of new ships and equipment throughout his 30-year career. He retired in 1966 as a Rear Admiral, having become Vice Chief of Naval Staff.

After his retirement from the Navy, he entered the aircraft related industry. He was a director of the Canadian Air Industry Association and president of his own air traffic control company for many years. He maintained naval connections serving as Honorary Chairman of the Navy League and participated in the Naval Officers Associations. His funeral was celebrated on Friday, June 4th at Victory Memorial Park Funeral Chapel, 14831 - 28 Avenue, Surrey, B.C.

Jun 2/10