By Thurlow E. (Buck) Arbuckle

Director, Telecommunications Division,

Department of External Affairs (Ret'd).

In the beginning, there was nothing. The fledgling Department of External

Affairs had a few embassies in such major centres as London, Paris, Washington

and New York and relied heavily on British services, i.e., The Diplomatic

Wireless Service and the Diplomatic Courier Service to carry correspondence.

In the early stirrings of communications, Washington and New York were

favoured with leased circuits and these were given a measure of security

with a device known as Telecrypton.

In the beginning, there was nothing. The fledgling Department of External

Affairs had a few embassies in such major centres as London, Paris, Washington

and New York and relied heavily on British services, i.e., The Diplomatic

Wireless Service and the Diplomatic Courier Service to carry correspondence.

In the early stirrings of communications, Washington and New York were

favoured with leased circuits and these were given a measure of security

with a device known as Telecrypton.

Supply and Services, a division of External Affairs, hired a few communicators and opened up a small section known as Communications. This comcentre was provided with book cipher, a tedious two-man system for encipher and similarly two for decipher. At embassies, secretaries frequently assisted in the process. One of the early communications in Ottawa was a gentleman who worked on book ciphers for one dollar a year while awaiting a suitable assignment as ambassador abroad. His name was Tommy Stone. This book cipher system involved looking up individual letters or words in code books and substituting them for five number groups which were then subtracted from another five number group. The result had to be typed for transmission, or, in decipher, typed for circulation. Maximum speed – perhaps five words per minute.

Those were lean years. Like school children, communicators were issued with a pencil and only when that pencil was worn down to 1½ inches could they turn it in for a new one. If it were necessary to visit another building on business, he could apply to Supply and Services for a bus ticket. But it was not all bad. Communicators as a group often found Prime Minister Mackenzie King 3. at the wicket enquiring about the status of a telegram. Many other senior officials in the department were well known to the communicators but were strangers elsewhere.

Anxious for something better, the comcentre acquired a British developed electro-mechanical device known as Typex. This Typex machine had many similarities to the German Enigma, developed before the Second World War, which proved very secure indeed. Typex used rotating code wheels with inserts and plug boards and the machine was programmed for each message. When the communicator typed into the machine it produced a printed result on a gummed tape. This tape was then stuck onto a page to be retyped for transmission or circulation. A good communicator with all the associated typing might process a message at an amazing 10 words per minute. This was a vast improvement on book cipher, less labour intensive, and less prone to error.

A peculiarity of the Typex system was that negatives were always repeated in telegrams to ensure the meaning was not lost through error to transmission corruptions. Vowels were omitted. The receiving communicator had to look at a string of consonants and reinsert vowels to try to re-establish a readable text for distribution. Most of the time, he accomplished just that. This procedure shortened the message, saved transmission time and costs which were increasingly important because communicators were filing more and more telegrams commercially via CN/CP Telecommunications. Sending coded telegrams commercially often meant that code groups were received corrupt, transposed or even omitted. Corruptions were the bane of communicators who spent much time seeking corrections and repeats in order to solve unintelligent portions of corrupt messages.

As communications improved, so the Department placed increasing dependency upon communicators. Dispatches through the diplomatic bag were slow and as they decreased, so comcentre traffic increased. More leased circuits were installed. Although the Department was limiting its use of the Diplomatic bag to send dispatches, the Canadian Diplomatic Courier Service was expanded to handle shipments of communications material.

About that time, in the late 1940’s, a new machine arrived on the scene. It was Rockex and it employed a measure of electronics in conjunction with mechanical drives. It was this machine which caused an establishment change. The little comcentre became a separate division, and, influenced by the influx of electronics, was renamed the Telecommunications Division. Over the years, perhaps two hundred Rockex were bought, which indicates the extent of the expansion of the communicators work at home and abroad.

The Rockex used a cryptographic key tape which, when combined with a paper tape input, produced either five letter groups or plain language text. This output was collected on a punched tape for transmission and on a page copy for distribution as necessary. These machines reduced the manual input of the communicator as compared to book cipher or Typex but there was still much typing and attendance on machines geared for sixty words per minute.

Traffic volumes multiplied. More and more circuits were leased. London and Paris were turned into relay centres, each relaying traffic for numerous area posts. New circuits meant more equipment and space in Ottawa, London and Paris comcentres was at a premium. Particularly in Ottawa, Communicators were stressed out running around the comcentre tending circuits. Tape relay equipment arrived and offered more compact work stations. This eased the situation somewhat but traffic volumes continued to increase relentlessly.

Rockex influenced other areas. Equipment had to be transported securely to embassies. Cryptographic key tape shipments to all posts were urgent and never ending. The Canadian Diplomatic Courier Service was extended to meet demands and communicators, who understood the requirement, were recruited into the service.

Soon Departmental expectations exceeded the current processing capacity of Rockex. Key generators seemed a promising alternative. Transparent to the communicators and hard wired into transmission circuits, they cruised at 100 words per minute. Communicators received telegrams from the various divisions, typed them into the communications format and simply transmitted them on the appropriate circuits. Key generators did the encryption and decryption automatically. These machines provided an added level of security in that they fed a continual stream of characters down the circuits whether or not there was any traffic. Thus any would-be interceptor was unable to tell when a message began or ended, or even whether a message was actually being transmitted.

But as one problem was solved others required attention. Many messages had multiple addresses. This demanded that a prepared message had to be transmitted on a number of circuits, increasing the handling time for a single message many times over. Message switches were new on the market and CN/CP Telecommunications were contracted to supply, program and install the necessary equipment. Communicators, with their experience and expertise in handling traffic were very much involved in programming and testing of the hardware. Leased circuits were established direct from Ottawa to most embassies and the relay operations in Paris and London were repatriated. Message switching was a huge success and acted as a spring board for future developments but it also retired a big chunk of the communicators work load.

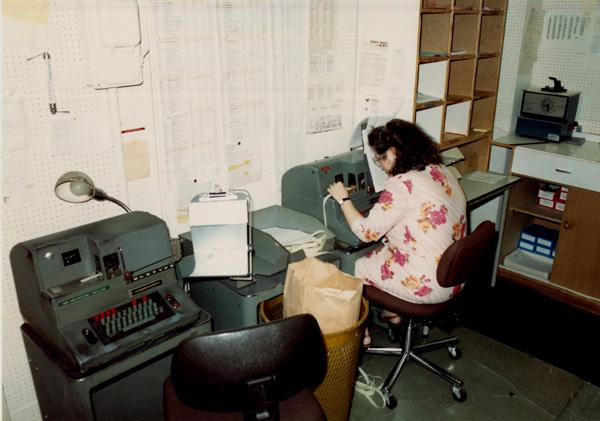

But typing was still a communicator’s chore. Telegrams were first typed by secretaries, then handed to communicators who they re-typed them into the communications format. Why not change the telegram form and have the secretary’s type telegrams in the communications format in the first place? Electronic readers were provided which read the new form and converted the telegram into electronic impulses for transmission. The communicator’s job was shrinking fast. The final blow came with a decision to move the telecommunications terminal out of the comcentre onto the desk of the Foreign Service Officer. These officers reluctantly became communicators and the communicators work was finished.

The Diplomatic Courier Service was also hit hard. No longer was it necessary to ship great quantities of classified communications material to posts, and, as electronic transmission replaced the need to dispatch many documents by bag, the courier service was largely disbanded.

Communicators had been called upon to tackle many different tasks and they met the challenge. Half of the officer complement of the division were former communicators. The divisional secretary was a reclassified communicator. Communicators figured prominently managing divisional accounts. The courier service was staffed by communicators who, in turn, took over the budgeting and management of the whole courier service.

Unfortunately, the communicator, who breathed life into the department, advanced and worked themselves right out of existence. But their 50 year contribution will always be remembered with admiration for their steadfast devotion and dedication to duty. In 1995, Parliament adopted legislation that formally recognized the name change from External Affairs Canada to Foreign Affairs Canada .

This list will summarize, in chronological order, the various crypto systems that were used by Foreign Affairs Canada (FAC) and including the present. For a historical perspective on this era, select this link.

In 1954, Lester B. Pearson, the Secretary of State For External

Affairs, began to realize that Canada

should begin an effort to provide all, but the smallest of diplomatic

posts, with cypher machinery in case an emergency should develop either

of local or general nature.

By March 1956, there was a concerted effort by FAC to introduce ciphered, teletype-based communications to replace the diplomatic pouch and improve the efficiency of sending messages. Colonel W.W Lockhart spearheaded this program which commenced in the summer of 1955. Once example of improving efficiency was to have a decoded message sent to a Teletype machine which would print on mimeograph (aka Ditto) paper. Numerous copies could then be produced and distributed from the master. In this time frame, the department's teletype equipment was on line 16 hours per day, 6 days per week. A one-half hour would be lost at the beginning and end of each day setting up new codes and shutting down the operation for the night.

(Table under construction)

| CRYPTO SYSTEM/MACHINE NAME |

|

|

| OTFP and OTLP | 1930's | Spring of 1984 (1) |

| Typex | 1946 | 1968 |

| BID 590 (Noreen) | 1962-63 | Early 1980's |

| Rockex | 1950's | 1983 |

| BID 610 (Alvis) | 1965 | November 1990 |

| CID-610 | 1965 | 1990 |

| STU-II Secure Phone | 1977 | 1986 (2) |

| BID 770 (Topic/Tenec) Note 5 | 1978 | 1992 |

| KG-30 | 1978 | 1988 |

| STU-III Secure Phone | 1986 | 2008 (2) |

| KL-43D | 1988 | 1991 (3) |

| Race | 1984 | Never put into active service |

| Aroflex | 1984 | 1989 |

| DUCS (Dial-up Crypto System) | April 1990 | 1992 (4) |

| KG-84C | 1988 | 2004 |

Notes:

1. OTFP and code books fell into disuse when electronic messaging systems came on-line, however, they were retained as a backup system in case OCAMS or NOCAMS was down for an extended period of time. Book Cypher remained at overseas missions until the early 90's.

2. Ray White indicates "The STU-II and later STU-III secure telephones were used in secure facsimile operations (SFAX). Prior to this, the KG-30 was for used for SFAX which was a point-to-point service and did not go through any message switch".

3. Made by TRW. It was also the last standalone crypto unit to be used by DFAIT before they switched over to the SIGNET system entirely. The KL-43D's were valued at US$225 each in 1994 but no more than a few units were purchased by the late 1980s.

4. No longer used when SIGNET came on-line. This date is in need of refinement.

5. Topic was the British name for BID770. Tenec was DFAIT's acronym which stood for "Telecom Equipment New for Embassies and Consulates.

NETWORKS USED BY FAC

Various crypto machines were being utilized at the times these networks

were in place.

| NETWORK NAME |

|

|

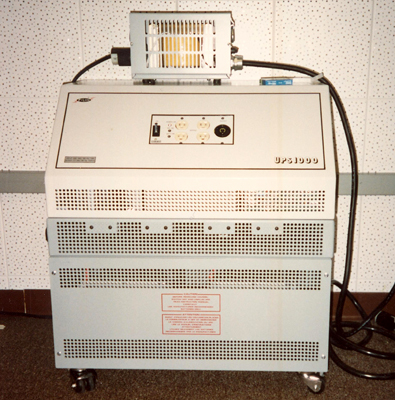

| OCAMS | Fall 1974 | Likely after 1978 to overlap with NOCAMS in-service date |

| NOCAMS | By 1978 | August 18, 1997 |

| COSICS | Phase 1- 1989 (DEC VAX based) | Dec 6, 1996 (Last message) |

| SIGNET | 1992 - First operational release.

1995 - Deployment completed worldwide. |

To present day |

Bob Brill who was the Deputy Director of Operations at the time, recalls the last messages sent by the NOCAMS system. "At approximately 1830 GMT August 18, 1997 the dear old servant NOCAMS served us for the final time. The activity was presided over by Tom O'Quinn when he downloaded the final messages to the LOG circuit. For Tom, it was difficult task, and for many others, a very sad event. NOCAMS served the Department well and those who managed her very complex operations provided tremendous service to the department. We shall remember NOCAMS as being "now that was a computer" as she was away ahead of her time. She led in the microcomputer era for governmental secure communications and certainly served CN/CP well in their development and exploitation of technology. I hope that someday one of the more knowledgeable will write a history on NOCAMS and all that she did".