CANADIAN WEATHER SHIPS

GENERAL

After World War II, the passenger aircraft replaced the passenger

liner for travel across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. With the advent

of this service, good weather forecasting became necessary. Actual weather

observations taken on a regular basis had to be performed from various

areas of these two oceans in order to develop forecasts. The world's major

political powers came together on this idea in London England and as a

result, Ocean Weather Stations (OWS) were created in 1946. Canada was placed

in a position of assisting the United States in manning one of these stations

in 1947. There were three major objectives for the OWS:

* To provide positional information for long range, propeller flights

over the Pacific and the Atlantic. ( Non Directional Beacon)

* Weather forecasting and measurement of winds aloft .

* For long range aircraft flight planning based on weather observations.

* Provide a communications hub.

These stations were designated at various positions throughout both

oceans and the positions chosen so as to fill the gaps where there were

no shipping lanes and from where no weather reports came. Each position

was assigned a letter for identification purposes. The first half of the

alphabet became the Atlantic areas and the second half, Pacific areas.

Canada and the United States were to share responsibities at Station Baker

until July 1/50 . That's the date when the USA took over full responsibility

of Baker. Since this undertaking became the responsibility of the International

Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) the International Telecommunication

Union (ITU) assigned a block of call signs for their use. This block spanned

from 4YA to 4YZ. The ships were not only to provide surface weather observations

but also of the upper air pressure, temperature, humidity, wind direction

and speed. They were also equipped for search and rescue operations for

both ships and aircraft.

|

| Station 'B' for Baker, as it was called in that era, was situated at

56.3°N, 51°W and was a shared responsibility between Canada and

the US until 1950.The collective call sign for any or all US Ocean station

vessels was NMMZ,

(Map courtesy MSN Encarta Maps) |

|

|

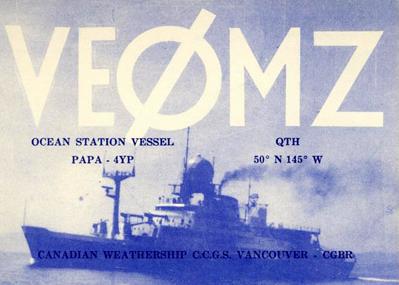

| Station 'P' for Peter (later called Papa) was Canada's exclusive

weather station at 50°N, 145°W from 1950 onwards. It was approximately

900 miles from Vancouver over water 4220 feet deep. The station was

operated from 19 December, 1949 through 20 June, 1981. (Map courtesy

MSN Encarta Maps) |

After one of the ICAO meetings, Canada was given the job of maintaining

station 'P' in the North Pacific and relinquished her half share in station

'B' mentioned above. Three of the River Class Frigates were taken over

by the Department of Transport, (DOT) extensively modified and crewed by

D.O.T. personnel. One Frigate was HMCS St. Stephen , a three-year veteran

of station 'B'. The other two were HMC Ships St. Catharines and Stone Town.

After the three ships were taken over by the DOT they became CGS St.

Catharines, CGS Stonetown [3] and CGS St. Stephen. The CGS stood for Canadian

Government Ship. All the DOT ships, the buoy vessels, icebreakers and so

on were known as CGS. They had civilian crews, were members of the DOT

and operated as a merchant ship. The personnel consisted of: Masters, Mates,

Engineers, Chief Stewards, Radio Officers, Electricians, Weather Observers

and any other trade that was needed to get the job done. Radio operators

were required to have their commercial deep sea radio certificate in order

to work for the Department of Transport.

The government of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker decided to consolidate

the duties of the Marine Service of the Department of Transport and on

January 28, 1962 the Canadian Coast Guard was formed as a subsidiary of

DOT. As a result, the three weather ships became Canadian Coast Guard Ships

along with the rest of the DOT fleet including the Buoy Vessels, Icebreakers

and so on. The crews remained the same as before. All the ships were repainted

with a red hull, white superstructure, white funnels with red maple leaf

on the funnel when their turn came up for refit after 1962. Before that,

all the ships sported a black hull, a white superstructure and a buff funnel

prior to 1962. Prior to the establishment of the Coast Guard, the organization

responsible for marine safety was the Canadian Marine Service (CMS).

The Coast Guard did not take over anything. Everything simply became

Coast Guard. Example - The CGS prefix for the ships became CCGS. The Captain

of CGS Tupper, the same man, became Captain of CCGS Tupper and wore the

same uniform, received the same pay and so on.

So how long was the rotation period while the ships were on station?

On the US side, a typical weather patrol was 21 days on-station plus enroute

time and about 10-days in port. It is believed that the Canadian rotational

period was similar when station 4YB began operations. One source stated

verbally it was 30 days for the Station 'B' era so there is some consistency

there. The CCG book USQUE-AD-MARE chapter on the weather ships indicates

that during the Stonetown / St Catharines era, rotations were on a six

week basis. Quadra /Vancouver did a rotation with seven weeks at sea and

five in their home port. The round-trip time consumed nearly a week.

After a seven week patrol, the crew had five weeks off.

Many of the single radio operators burned their "off time" in Mexico while

others would just get visit home. Others would r travel ariubd the

country. That work cycle was an attraction to some.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF OCEAN STATION PAPA

Latitude 50° 00' N, 145° 00' W

* Continuously transmits the Morse identification letters YP (

_._ _ ._ _.) on 391 KHz plus a two letter position signal indicating

the ship's position within the 10 mile grid square

* Guards 118.1 and 140.58 (voice) and CW frequencies of 4742.5, 6557,

8280, and 500 KHz.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF OCEAN STATION BAKER

Latitude 56° 30' N, 61° 00' W

* Continuously transmits the Morse identification letters YB (

_._ _ _. . .) on 391 KHz plus a two letter position signal indicating

the ship's position within the 10 mile grid square.

* Hours of transmission: At 5, 20, 35 and 50 minutes past each hour

and on request.

Ocean station ships were always underway . They never drifted within

their assigned grid square. The power output of the ocean station beacons

was likely in the neighbourhood of 200 to 300 watts. The transmitter fed

a horizontal long wire strung out from the bow to the bridge.

The weather ships were staffed with a crew of around 40 but this could

vary plus or minus depending on the scientific experiments that were being

carried out.

WEATHER SHIP CHRONOLOGY

HMCS WOODSTOCK

There were several Canadian warships sent out as Weather Reporting Ships

to various parts of the world's oceans during World War II. Canada's first

weather observation ship was the Flower Class corvette Woodstock K238,

radio call sign CYQZ. On January 27, 1945, she was paid off in Esquimalt

for conversion to a loop layer but upon recommissioning on May 17, she

was employed as a weather observation ship and shared a patrol with United

States ships some 500 miles westward of Vancouver Island. Woodstock's weather

observation services predated the international World Meteorological Organization

(WMO) agreement of 1946 . The ship finally paid off on March 18, 1946.

|

| HMCS Woodstock in her WWII camouflage. (Photo courtesy Naval Museum

of Manitoba) |

HMCS ST. STEPHEN

The Royal Canadian Navy had to supply a ship for weather station 4YB

so they assigned the River Class Frigate HMCS St. Stephen. She carried

out these duties on a rotational basis with an American ship from Sept

27, 1947 to August 1950. Since the weather branch of the Canadian government

was a part of the Air Section of the Department of Transport (D.O.T.),

St. Stephen was crewed by a complement of some ninety officers and ships

company, and a civilian staff of five Department of Transport meteorological

observers.

|

| ST. STEPHEN as a weather ship. (Image courtesy Frigates

of the RCN 1943-1974) |

|

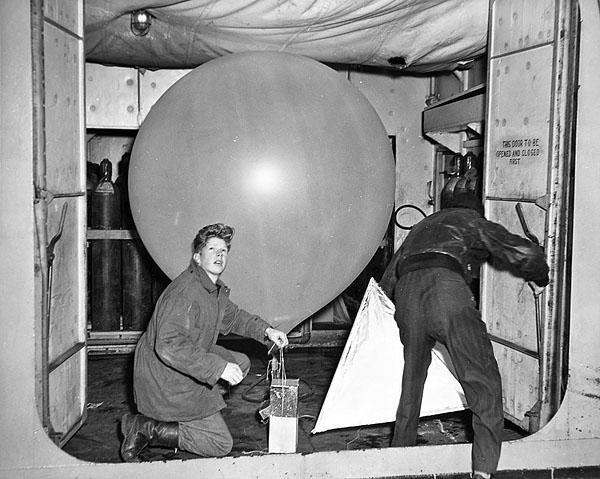

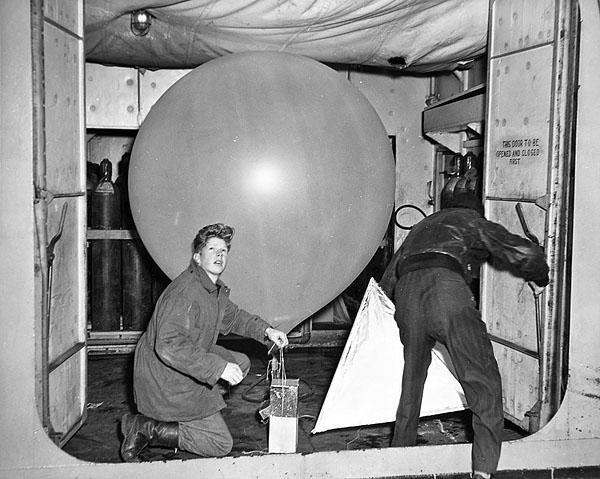

| A weather balloon being inflated aboard ST. STEPHEN at Baker

station. Also shown is the radiosonde and the radar reflector. Note the

padded deckhead to ensure nothing can puncture the balloon. (Photo

believed to be taken by W.S. Walker via Sandy McClearn) |

|

| Some naval references indentify St. Stephen as having pendant 323.

This is incorrect. In the inset, this photo clearly associates the name

of St. Stephen to pendant 302. (Photo via Sandy McClure) |

Paid off from the navy in 1950, St. Stephen was sent to Esquimalt

to be loaned to the Department of Transport (DOT) for use as a weather

ship and assigned call sign CGGR. Ultimately she was retained primarily

as a "spares" ship in the event of a mishap to Stonetown or St. Catharines.

St. Stephen never left port. In spite of never filling the role as

a backup ship, she was nonetheless refitted in 1955 and remained berthed

in Victoria. St. Stephen was purchased by the DOT in 1958 and retained

for another 10 years until she was sold to a Vancouver buyer purportedly

for conversion to a fish factory ship. Stories about the St. Stephen which

appeared in Crowsnest Magazine can be found here.

ST. CATHARINES

Paid off from the RCN on November 18, 1945, St. Catharines was sold

to Marine Industries Ltd, and laid up at Sorel, Quebec until purchased

by the Department of Transport in 1950 and converted to a weather ship.

She was then transferred to the west coast where she took up station 'P'

in December 1950 under the command of Captain J. S. Sleight. Her

call sign was CGGQ . Jointly with Stonetown, these two ships provided

this service for sixteen continuous years. In March 1967, St. Catharines

was replaced by CGS Vancouver and was then broken up in Japan in 1968.

|

| CCGS St.Catharines, call sign CGGQ. Her radar antenna is the

'AUK' type which means the ship is fitted with the 277P radar. Note the

flush deck and modernized bridge. It's estimated that this photo was taken

between 1962 and 1967. (Canadian Coast Guard photograph submitted

by Spud Roscoe) |

CCGS STONETOWN (nee STONE TOWN)

When part of the RCN, the ship was named Stone Town. After transferring

ownership to DOT, the name became (MISSPELLED TO) Stonetown..The

misspelled name will be retained in the text that follows because that

is the way the letters were welded to the bow. The amateur radioo station

also used the Stonetown name in its mispelled form.

While being tropicalized at Lunenburg, NS for service in the Pacific,

WWII ended and the work on HMCS Stone Town was stopped on August 24, 1945.

After being paid off in November of that year, she was laid up in Shelburne

NS for a while before being sold to the Department of Transport for use

as a weather ship. She was modified for that purpose at Halifax in 1950

and in October of that year, CCGS Stonetown sailed to Esquimalt for duties

at weather station 'P'. The ship's assigned called sign was CGGP.

Some naval reference books indicate HMCS Stone Town as having pendant

302. This is incorrect. She was paid off after WWII and was never re-commissioned

having been sold to the Department Of Transport. Pendant 302 was actually

assigned to St. Stephen. Stonetown was CGS Stonetown [3] from 1950 until

1962 and then she was CCGS Stonetown until scrapped.

|

This aerial photo of Stonetown is one of the

best. Click on image to enlarge. (Canadian Coast Guard photo) |

SPECIFICATIONS FOR ST. CATHERINES and STONETOWN

Length: 301 ft. 6 in.

Beam: 36 ft 7 in.

Draught: 12 ft. 9 in: (mean)

Displacement: 1,883 gross tons

In June 1952, twice-daily bathythermograph casts were initiated

at Station P and continued to June 1981. By July 1956, oceanographic observations

including hydrographic casts to maximum depth of 1200 metres (m), plankton

hauls, etc. commenced. They were scheduled for one of the two weather

ships and provided data for alternate six-week periods. The maximum was

increased to 2000 metres later but only in a few instances did the cast

reach 2000 metres during 1957 through 1959. However, one cast to 3000 metres

was recorded in 1957. By March 1960, maximum depth of hydrographic casts

at Station P increased to 4200 metres.

Barry Hastings who served on weather ships provides some information

on staffing and work assignments. "Both the old and new ships carried the

same total complement of roughly 50 personnel. This would include 9 radio

operators, 7 upper air meteorologists one, often two oceanographers from

the Pacific Oceanographic Group. There were no Radio Electronics technicians

on the old ships, only the newer ones.

Within the radio group, there was one Officer In Charge (OIC)

, and two radio operators doing radar ops and maintenance. One was

on a day watch; the other on night watch. The remainder were watch keepers.

There were always 2 operators in the radio shack. One held down the Aeronautical

position (and its other duties), while the other operated CW on 4,

6, 8, 12, 16, and 22 MHz and monitored the marine bands.

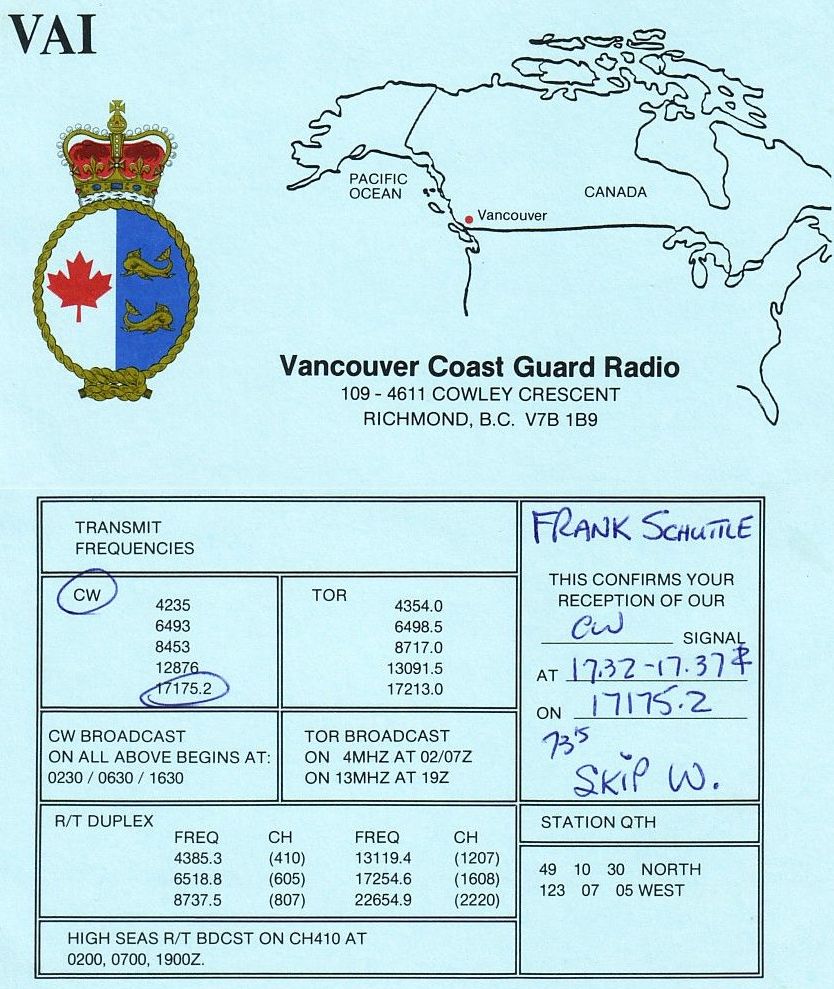

In addition, the watch keeper was responsible for meeting scheduled

radio facsimile reception times to obtain weather maps from either Honolulu

or San Francisco. The Marine Position guarded 500 KHz and voice 2182 KHz

along with providing point to point communications with Vancouver Radio

VAI.

The old frigates did not carry a ship-shore telephone system which would

enable crew to call home. That was fitted on the new replacement ships.

The only communications for crew and family was a letter which was termed

a “radio deadhead” message. A Deadhead classification indicated there

was no charge (like a paid-for ship to shore radiotelegram). Both

families ashore and crew were asked to keep the quota to one letter a week

and the message no longer than 25 words in length. Radio deadhead CW traffic

from Radio VAI was sent usually sent to the ship during the 0400-0800 watch.

Messages from the ship to VAI were generally sent on the 0000-0400 watch.

All business, ship, meteorological, personal mail etc was sent in CW on

the old frigates. When the newer ships came into service, radioteletype

would serve this function.

In the aeronautical position, the operator was responsible for “being

aware” of various flights but with particular attention to aircraft that

might come in range of our radar for plot purposes (ie within 100 NM).

With an impending aircraft approach, he/she would alert the on duty

radar operator who would go into the radar Ops room and start searching

in the appropriate quadrant. Once targeted, the operator would give

readouts to the bridge who would do a manual plot. This was usually done

by the Bridge Officer. With several readings, he could then give a track

and ground speed interpolation report.

The marine radio officers on the 2nd and 3rd watches copied

the plain language High Seas Forecast from San Francisco Radio KFS.

Each day, there was an early morning and evening plain language forecast.

This gave the various locations of high and low pressure systems, frontal

systems, anticipated gale, storm or hurricane force winds. Ocean

Station Papa had one of the "best" locations of probably all the OSV’s.

Best meaning right in the middle of air circulation patterns, 900 miles

out fropm land and south of Alaska. This was the perfect recipe for the

creation of gales, storms and hurricane force winds. Summer wasn’t bad,

but in the winter months we always had a good ride!!”

Some OWS ships volunteered to carry out surface weather observations

while enroute. This would include precipitation, visibility, sea conditions,

wind direction and speed along with latitude and longitude. This information

would be coded into 5 figure groups. There would be about 12 to 13 groups

per observation. The 24 hour clock is divided into 6 hour groups, each

called a major synoptic. The lesser synoptic is groups of 3 hours. Volunteer

ships only sent reports during the major synoptics. If the ship was within

range on 500 KHz, the operator would call until he was answered and given

a turn on the working frequency. The OBS report was then sent to an OSV.

Every trip out and back, the ships carried out ocean studies. I forget

how many stations were involved, but about every 6 to 8 hours we dropped

a cable to which bathometer bottles were attached. With this arrangement,

we studied depth temperatures, plankton levels , etc . While on station,

there was also a similar program carried out daily. We also released four

radiosondes per day which provided met data up to 50,000 feet.

Meteorologists aboard the weather ships were called “upper air”

Met Officers. They not only made surface observations, but released

the massive balloons which carried a radiosonde transmitter and radar reflector.

Getting that massive balloon and its trailing equipment was quite a challenge

particularly in high winds and high seas. When inflated using helium, they

were quite large. Timing was everything. As the stern dropped in

the seas, it was release time. If you didn’t do it right, the radiosonde

transmitter might hit the ships rail. Once released, the radar operator

would acquire it as quickly as possible, giving distance and elevation.

The sonode equipment would be transmitting data on air pressure and temperature

back to the Met shack. As each specific report was compiled, a meteorologist

would deliver them to the radio room. Some of the reports were an

average of thirty 5 figure groups to a message, some 50 groups or more.

The marine position now sent those messages via CW to Radio VAI.

There were a few operators who preferred a hand key (and were very good),

but the majority of us used Vibroplexes".

In October 1967, after 17 years of being on station in the North Pacific,

Stonetown was replaced by CGS Quadra, and then sold in 1968 to a Vancouver

buyer, purportedly for a conversion to a fish factory ship.

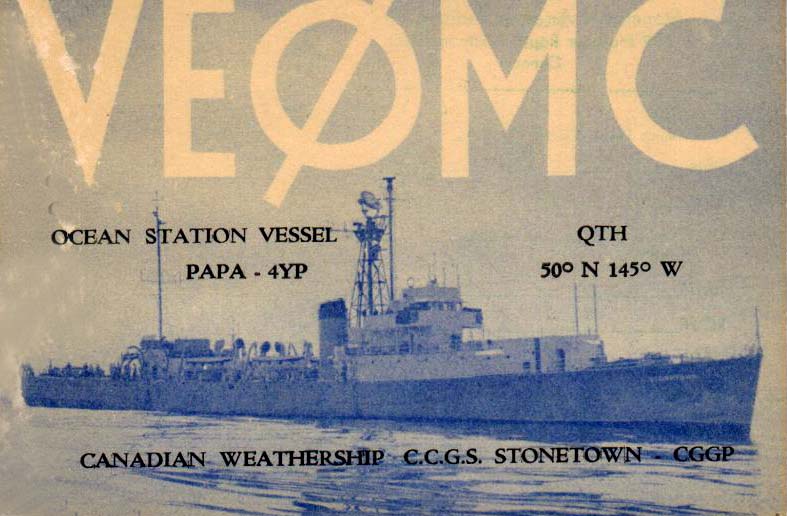

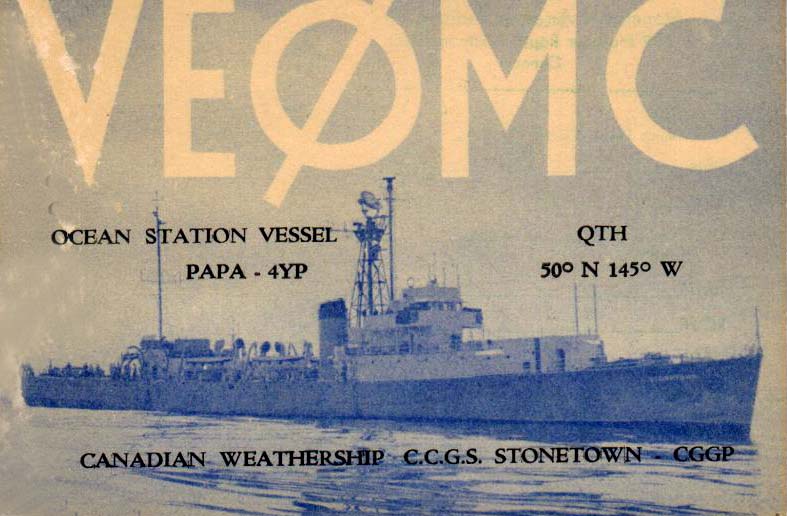

While in service, Stonetown had an amateur radio operation aboard. Call

sign VE0MC was registered to C.M.S. Stonetown Amateur Radio Club, Victoria

BC with Jack Scarlet as the station sponsor,. There is one report

of a confirmed contact with the ship at 0307 GMT on July 10th, 1962, on

14130 kHz using Upper Side Band. It is also confirmed that St. Catherines

and Stonetown operated VE0MZ and VE0MP [2] respectively. These call

signs were transferred to CCGS Vancouver and CCGS Quadra (respectively)

when the old ships were retired.

Back in those days, the VE0 prefix was assigned to a club with a sponsor

and the sponsor was accountable for all activities of the station. In a

Canadian port, a VE0Mx call could operate just like any other amateur station.

When the ship was beyond the Canadian 3 mile territorial limit, operation

was restricted to 14000 to 14250 kHz on 20 meters and any frequency in

the 15 and 10 meter bands. In order to operate in the US or US territorial

waters, the station sponsor had to secure a special card from the FCC.

|

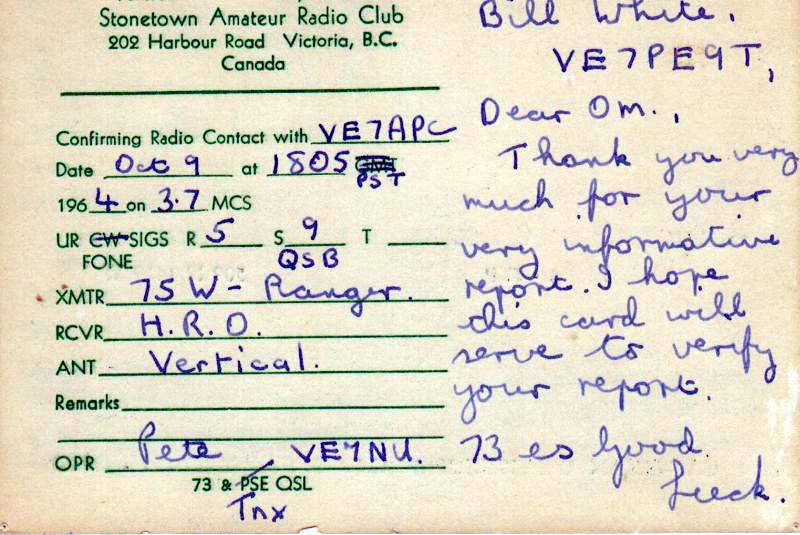

| VE0MC - front of QSL card. |

|

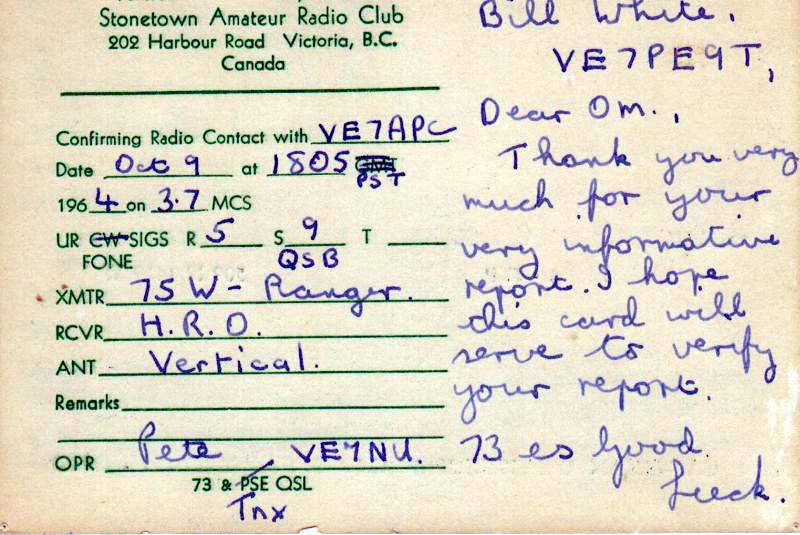

| VE0MC QSL, reverse side. Bill White (now

VE1CY) was a Short Wave Listener under the Popular Electronics magazine

SWL program. His registration registration number was VE7PE9T. Here, he

monitored communications between VE0MC and VE7APC. By providing a signal

report, he received a QSL from VE0MC. |

|

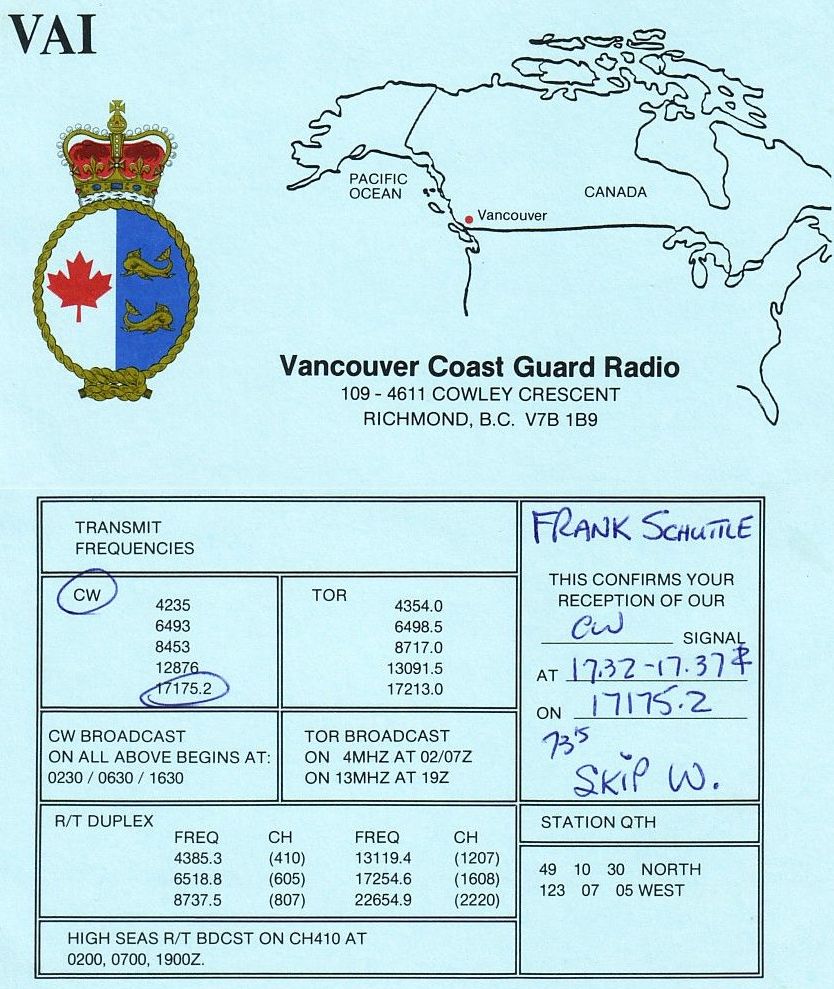

| This signal verification report from coastal station VAI provides a

glimpse of what frequencies were used in radio communications with the

weather ships. TOR means Teletype Over Radio. Click on image to enlarge,

(Image

provided by Frank Statham) |

|

| CCGS Stonetown outboard of CCGS St. Stephen. Stonetown is fitted with

her 277P radar as attested by aerial outfit 'AUK'. Because St. Stephen

had become a parts source to support the other two ships still in service,

she never left port. Notice the missing 277 antenna on her foremast when

compared to Stonetown. (Canadian Coast Guard photograph submitted

by Spud Roscoe VE1BC) |

By 1970, the WMO was assigned the block of calls C7A to C7Z and

the reason was not clear as to why an additional block of call signs was

even necessary. The only C call sign ever heard was C7H. By 1948, all U.S.

stations were manned continuously except Station H. That station

was operated only from 1952-54 and again from 1971-76. It is speculated

that this may be the reason for using the C7H call sign rather than 4YH.

Each station was identified with a letter and this letter was the suffix

of the call sign. There were seventeen stations only so one would assume

the ICAO 4YA to 4YZ calls would have been sufficient. The stations were

called by the same names as used in the International Phonetic alphabet.

This alphabet was altered from time to time so Station B was referred to

as Baker initially, then later as Bravo. Similarly station P started

off as Peter and ended as Papa. To see how the phonetic alphabet evolved,

select

this link. The station assignments are summarized in the

following table and map:

|

| Ocean weather stations by location. After their establishment, they

started to slowly disappear. An ICAO commitment basically kept 4YP and

4YN in the Pacific active. A typical reliable range for a beacon signal

was 200+ miles. (Graphic courtesy Wood's Hole Oceanographic Institute) |

|

ATLANTIC STATIONS

|

|

PACIFIC STATIONS

|

|

|

| STATION |

POSITION |

OBSERVER |

FREQ |

|

STATION |

POSITION |

OBSERVER |

FREQ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4YA |

62N 33W |

USA & Netherlands |

|

|

4YN |

32.3N 135W |

USA |

385 kHz |

| 4YB |

56.3N 51W |

USA (shared wuth Canada until 1950) |

391 KHz |

|

4YP |

50N 145W |

Canada |

391 KHz |

| 4YC |

52.45N 35.3W |

USA |

385 KHz |

|

4YQ |

43N 167W |

USA |

328 KHz |

| 4YD |

44N 41W |

USA |

350 KHz |

|

4YS |

48N 162E |

USA |

|

| 4YE |

35N 48W |

USA |

|

|

4YU |

27.4N 145W |

USA |

|

| 4YH |

36.4N 69.35W |

USA |

|

|

4YV |

31N 164E |

USA |

|

| 4YI |

59N 19W |

Great Britain |

|

|

4YX |

39N 153E |

Japan |

|

| 4YJ |

52.3N 20W |

Great Britain & Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4YK |

45N 16W |

France & Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4YM |

66N 2E |

Norway |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The United States built 98 ships from the plans of the River

Class Frigates and called them the Tacoma Class Patrol Frigates. They were

naval ships as in USS but they had U.S. Coast Guard crews. As a matter

of fact the first two, PF1 Asheville and PF2 Natchez were built in Canada.

Some of these Patrol Frigates were used as weather vessels during the war.

Many vessels assigned these ocean stations after the war were these former

Patrol Frigates.

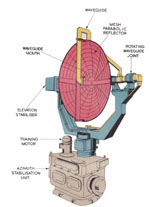

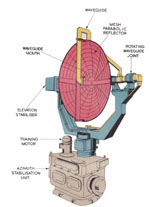

Barry Hastings was one of the Radio Officers in the three former Frigates

assigned to station P. He describes the radar fit. “The radar equipment

aboard the River Class frigates St. Catherines and Stonetown, which manned

4YP for many years, was the British designed type 277Q [1]. With

all the right adjustments one could track an aircraft but this was really

tricky. We used to do aircraft plots on these rigs while on station 4YP

and we got pretty good at it. Propeller aircraft were typically tracked

up to 80 miles and on occasion 95 miles but all we could get on him

was a quick bearing, distance and that was all. "

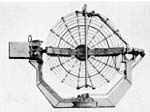

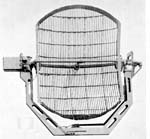

277 RADAR PHOTOS

|

A typical 277 Office. Click to enlarge. 1 - PPI

Display; 2 - 'A' Display; 3 - HPI display; 4 - Aerial bearing

indicator. Click to enlarge. (Courtesy CB 4182/45

Radar Manual via Øyvind Garvik ) |

|

277P Aerial Outfit 'AUK'. Click to enlarge. (Courtesy

CB 4182/45 Radar Manual via Øyvind Garvik ) |

|

277P aerial from a slightly different angle.

Click to enlarge. From B.R. 1853 Radar Manual Volume I, 1953. (Submitted

by Øyvind Garvik) |

|

277Q aerial. Click to enlarge. From B.R. 1853

Radar Manual Volume I, 1953. (Submitted by Øyvind Garvik) |

|

277Q radar installation on either Stonetown or

St. Catharines. (From the collection of Frank Statham) |

On a map, an Ocean Station was an area 100 nautical miles E-W

and 100 nautical miles N-S divided into 10 nautical mile squares.

The center square, which the ship usually occupied, was designated

“OS” meaning “on-station”. If the ship drifted off by 10 nautical

miles, the captain had the ship moved back to OS. This could be quite

challenging when the weather was bad because the ship acted like

a sail.

Weather ships had a radio beacon transmitting the call sign of

the station in Morse code and the square in which the ship was located.

For this function, Canadian weather ships used an endless loop of tape

to key the transmitter. Overflying aircraft would check in with the ship

and receive its position, course and speed by radar tracking, and weather

data. When on station, a ship had to stay within a ten-square mile area

of the assigned position. Once the ship was outside the boundaries of the

station area, the beacon would be shut off.

Barry Hastings confirms the beacon ID. " The beacon identification for

4YP were the letters YP followed by the two identifying grid letters.

Aeronautical radio beacons were assigned individual frequencies and the

two letter identification would provide positive identification of the

beacon.

Those who communicated with the River Class frigates will best remember

them by the call sign 4YP.

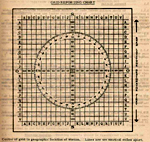

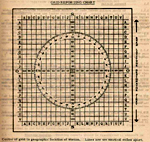

DETERMING THE GRID SQUARE TO BE TRANSMITTED BY THE BEACON

|

GRID REPORTING CHART. As one

can see, the ocean station was a grid marked off in 10 nautical mile squares

and 100 nm in each direction. Each square had a unique two letter

identifier, with OS being the 10 nm square which held the 'charted position'

so to speak. For station P, it was 50N, 145W. If the vessel was in

that square, the radio beacon transmitted an OS identifier. If the

weather ship drifted to the north east, the identifier would be changed

to JK or something approximate.Click to enlarge. (Taken from Ocean Station

Vessel Manual, 1970. Provided by Frank Statham)

It is believed that the navigator had a chart of station Papa which

showed the lines of latitude and longitude surrounding the station.

Overlaid on this chart was a transparent, pre-marked Grid Reporting

Chart . Latitude and longitude were first determined by Loran “A”

or sextant in the early days . The resultant lat/long values would be looked

up on the chart . Immediately, that indicated the current grid

square of the ship’s position. The two digit grid square would then

be sent down to the radio office where the operator would change the position

code letters sent by the beacon transmitter.

Mariners or airborne navigators using PAPA’s beacon for navigation

would need an identical setup and use a reverse procedure. Cloudy

days made for bad celestial observations. At times, the ship’s position

was dead reckoned. They had no idea of where they were.

The beacon transmitter was a deck down from the radio room and forward.

Its keyer consisted of a moving bicycle chain device on the bulkhead in

the radio room. By manipulating knobs on the chain, the code could

be altered.

The latitude and longitude of the ship was checked by the bridge at

hourly intervals. Any change from the previous reading would be called

into the radio room and inform the operator that the ship was now in grid

square xy. The radio operator would go over to the beacon keyer which

hung on the bulkhead and twisted in the new code. |

END OF SERVICE LIFE

|

| Taken from the aft deck of either CCGS Vancouver or Quadra, post 1967,

two of the old weather ships await disposal at the Esquimalt Graving Dock.

This is where the weather ships normally berthed when they were in service.

The outboard ship is St. Catherines. Tied to the dock is either St. Stephen

or Stonetown. Click on image to enlarge. (Photo by Jack Cain) |

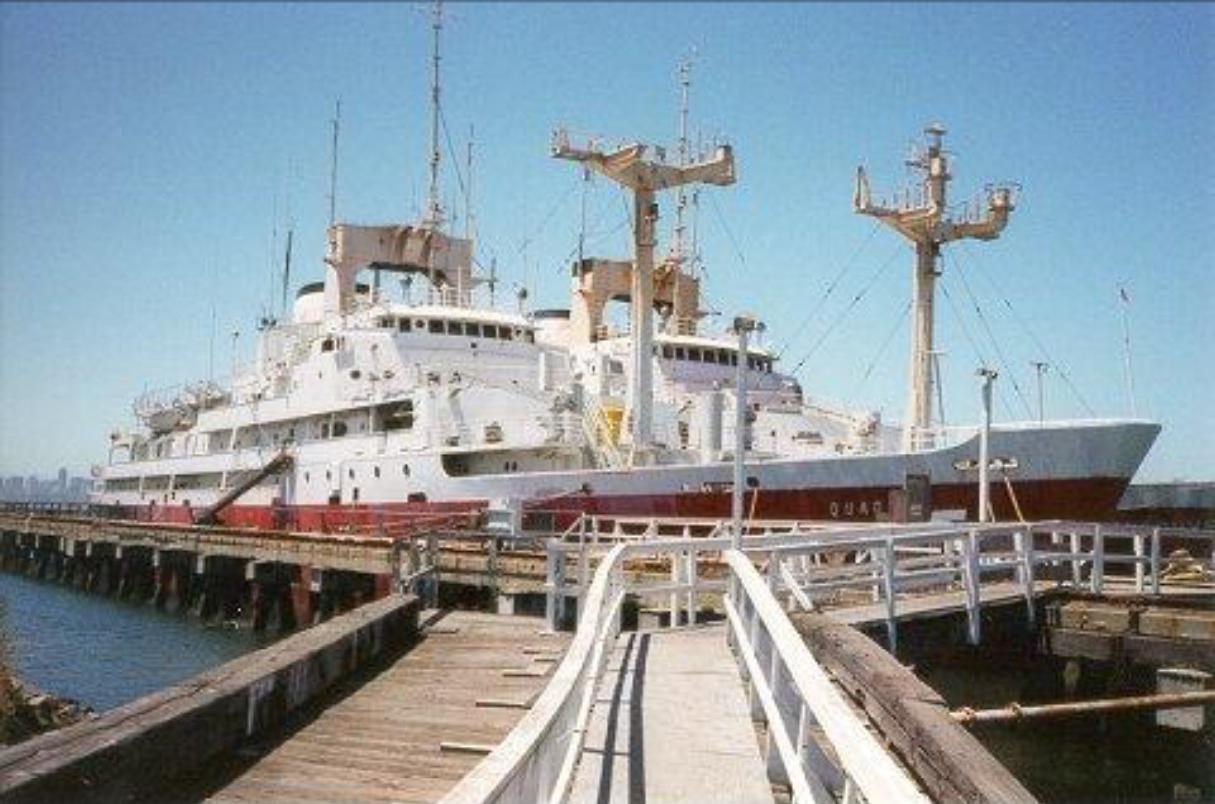

REPLACEMENT SHIPS - CCGS VANCOUVER and QUADRA

This excerpt from the Coast Guard web page provides the final chapter

in the history of the weather ships.

"By 1960 the Department (of Transport) began to consider the question

of replacements and, in 1962, tenders were called for two very advanced

weather ships. These were Vancouver and Quadra, which were put into service

in 1966 and 1967 and replaced St. Catharines and Stonetown respectively.

These two ships were of steam turbo-electric twin screw propulsion

and had an endurance of 8,400 miles at a cruising speed of 14 knots. Although

they could steam at 18 knots, the work called for a high degree

of mobility at very low speeds and the vessels were therefore designed

as stable, and very manoeuvrable, platforms with highly complex equipment.

To obtain measurements of the temperature, pressure and relative humidity

of the upper atmosphere, balloons were released at intervals of six hours.

These balloons contained radio equipment that transmitted the required

information, the balloon itself was tracked by a radar installation that

fed azimuth, elevation and range into a computer that automatically produced

printed charts of upper wind speeds and direction. In addition the weather

ships maintained constant records of other meteorological and oceanographic

phenomena and provided a radio beacon aid to trans-Pacific aircraft.

|

| CCGS Vancouver. Inside the radome is the Sperry

AN/FPQ-10 radar used for tracking weather balloons. (Photo courtesy

Canadian Coast Guard) |

Operating in rotation with seven weeks at sea and five in their

home port of Victoria, the Vancouver, Captain Linggard, and the Quadra,

Captain Dykes, provided an unusual routine. The work at sea was constant

and meticulous. Ships and men were always ready to provide search and rescue

help in case of disaster to an aircraft or ship within reach. All on board

were able to function efficiently and harmoniously within the confines

of shipboard life, conditions that required high personal qualities because

the weather in that area of the North Pacific was always stressful on the

crew. The prevalent conditions usually included a heavy swell or sea, low

visibility, and a general lack of sunshine."

Mike Ball, who was an oiler aboard Vancouver shares his experiences.

"After spending a year aboard CCGS Estevan as a fireman, I transferred

to CCGS Vancouver as an oiler and made two trips to ocean station Papa,

in September/October and again in November/December, 1968. I used to borrow

a short wave radio receiver from the Third Cook, take it up to the balloon

hanger late at night and listen to radio stations as far as Texas and the

eastern seaboard of the US, Russia and the Far East. On the first trip

we did enjoy sunshine and no waves, just a low swell rolling in from the

west, but we also went through a few gales. After one overnight gale the

jackstaff was found to have been bent horizontal to the deck - this was

a 2" or 2 1/2" steel pipe with 1/2" rod stays down to the bulwarks, yet

the weather had not seemed too extreme during the course of the night.

The Vancouver and Quadra were wet ships in heavy weather, with the main

deck being out of bounds due to their ability to ship green seas over bow

and stern. The story was that after Burrard's was awarded the contract

to build Vancouver and Quadra, their designers were reviewing the plans

and discovered that if they built the ships with steel houseworks as designed,

they would capsize on launching. Needless to say there was a lot of hurried

communication between Burrard's and Ottawa with the result that the house,

from the main deck up, was to be built of aluminum. Later, on departing

the dock for sea trials, the Vancouver promptly heeled over and stayed

there, whereupon the inspectors onboard told the Master to return to the

dock and secure the ship until the stability problem was resolved.

It was - by pouring some 500 tons of concrete into # 1 and # 7 double

bottom tanks. Since these were originally to be used as fuel tanks, the

ship's steaming range was naturally reduced. It was the practice to add

ballast water to the double bottom fuel tanks as fuel was transferred out

to the settling tanks, and during this transfer the flume tank anti-rolling

system had to be shut down. I was told that the original design for the

new ships, developed by a couple of the Masters from the old weather ships,

was very well thought out and would have been good seaboats. However, the

various scientific departments all demanded special facilities be provided

and so the ships grew in size.

They were both supposed to carry two 20' (approx.) launches in davits

fitted forward of the wheel house, to be used by marine biologists and

other scientists for making day trips away from the ship for sampling purposes.

Only two of the launches were built as far as I know, one becoming the

Victoria Harbour Master's launch and the other being sold to private concerns.

The davits for these boats were never fitted, a consequence of the stability

issues the ships had. They could roll quite easily, anti-rolling flume

system notwithstanding.

On the first trip I made on the Vancouver, I can recall seeing the Mate

and Bosun going around checking the aluminum house sides and marking new

cracks with coloured crayon, and they were into the 70's. On return to

Esquimalt, the wet lab bulkheads were removed and replaced - all while

I was trying to sleep in my cabin four decks below having been assigned

to the midnight to eight watch."

Barry Hastings provides operational information on CCGS Quadra and Vancouver.

"For crew staffing, it was the basically the same as the old ships

except we now carried two Radio Electronic Technicians. The new radar system

and other electronics had automated a lot of the tasks formerly performed

by the radio operators. Because of that, there were some additional duties

added.

The Marine Position now manned the radioteletype (RTTY) and the ship-shore

telephone system. Even though we had RTTY, CW was still essential

due to the unreliability of the RTTY equipment which operated on

HF in the 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, and 22 MHz. bands It was not a “handshake”

system whereby the transmitters would exchange signals, confirm signal

compatibility, do corrections etc. We would cut a Baudot test tape and

send our test message which was the continuous letters RYRYRYRY TEST etc.

If received correctly, the communicator at radio VAI might send back an

acknowledgment to send traffic IF…and I do mean IF… it was garbling…the

radio operator at Vancouver would call us on HF voice or CW and try

request than another channel be used. Again, the RYRY test message

would be sent. If communication on RTTY could not be established, the ship

would ask if anyone at VAI can copy a spark gap transmitter. This either

elicited a laugh from VAI or an obscenity response. The new SSB ship/shore

telephone operated on HF in the 4, 6, 8, 12, 17, and 22 MHz bands.

Crew were again limited to one phone call a week with a 5 minute maximum

duration.

|

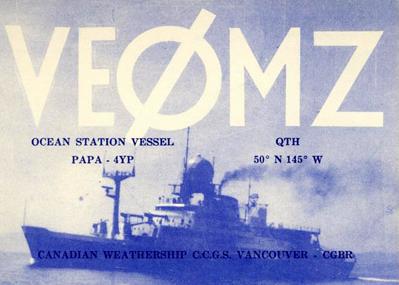

| This was the QSL card used by the Vancouver's Amateur Radio Club. The

station was fitted with Collins "S" line equipment running 600 watts into

a 35 foot vertical antenna. (QSL card image provided by Barry

Hastings). |

With the new ships came a better tracking radar in the form of the AN/FPQ-10.

The radar antenna was housed under the giant radome over the wheelhouse.

(The system was originally designed to track rockets at Cape Canaveral,

but it didn't prove efficient for that project). When the radio operator

(radar) targeted the upper wind balloon on launch, you could lock the radar

on and it would do all the tracking. A computer generated all the

data on distance, elevation azimuth etc. When targeting an aircraft,

it would provide constant readouts on track and ground speed. The only

minor problem was when the antenna was on its back (high elevation angle).

If it lost the target, the antenna would drop back to its stops (full

down position). Imagine the noise made in the wheelhouse when a 9

ton antenna would come crashing onto its stops. When it happened we would

get the most obscene phone calls from the bridge officer who was no doubt

shaking in his boots by this time!

When not on station. CCGS Vancouver used her normal call sign CGBR

The ship was assigned VE0MZ as a permanent amatuer radio call sign and

held it until her retirement"

Quadra and Vancouver radio rooms were fitted with Marconi (UK) Crusader

transmitters. Each ship was fitted with two transmitters One was at the

Aeradio operating position, and the other at the Marine position. Reports

indicate they were not user friendly to work on.. . The Crusader

at the Aeradio position was fudged to make it work on the air to ground

HF frequencies--odd number bands--5 mHz was one--while the marine bands

were all the even numbered-- 2, 4, 8, 12 MHz etc.

Between April and October 1974, CSS Parizeau replaced CCGS Quadra while

the latter was occupied with the GATE program.

BEACON STATION

All the weather ships for ocean station 4YP were fitted with transmitters

to act as a homing beacon for aircraft or ships on 391 KHz. Transmissions

were continuous and used MCW (A2) mode. The transmitted signal was -.--

.--. (YP) plus two position

letters. The ships maintained station at 50.00° N, 145.00°

W. The two position letters indicate the position of the beacon with a

10 mile grid square as shown above. Whenever a ship was under way

and homing in on a weather ship's beacon, it was necessary to be

very vigilant so as not to collide with the weather ship.

SHIP'S SPECIFICATIONS

VANCOUVER

Type: Weather ship, twin screw, steam turbine

Launch Date: June 29, 1965

Completion Date: July 1965

Ready for service: 1966

Builder: Burrard Dry Dock, North Vancouver

Overal Length 123.2 meters (Length between perpendiculars: 110

meters)

Beam: 15.3 meters

Draught: 17.5 feet

Displacement 5537 tons

Horsepower: 2 x 3750 SHP

Speed 14 knots crusing; 18 knots top speed

Endurance: 8,400 nm at 14 knots

Vancouver and Quadra Vital Statistics via Miramar Ship Registry,

New Zealand

QUADRA

Type: Weather ship, twin screw, steam turbine

Launch Date: July 4, 1966

Completion Date: April 1967

Ready for service: 1967

Builder: Burrard Dry Dock, North Vancouver

Overal Length 123.2 meters (Length between perpendiculars: 110

meters)

Beam: 15.3 meters

Draught: 17.5 feet

Displacement 5536 tons

Horsepower: 2 x 3750 SHP

Speed 14 knots crusing; 18 knots top speed

Endurance: 8,400 nm at 14 knots

END OF SERVICE

Vancouver and Quadra saw their last weather service in 1981 when ocean

station 'P' was terminated. A final series of observations was made by

CCGS Quadra in June 1981. Modern technology rendered the weather ship obsolete.

It was to be the end of an era. The Miramar Ship Index shows that Quadra

sank in tow on November 1, 2002 at Lat 30.58N Long 138.22W. As of

September 2010, Vancouver is in China awaiting her fate in the breaker's

yard.

|

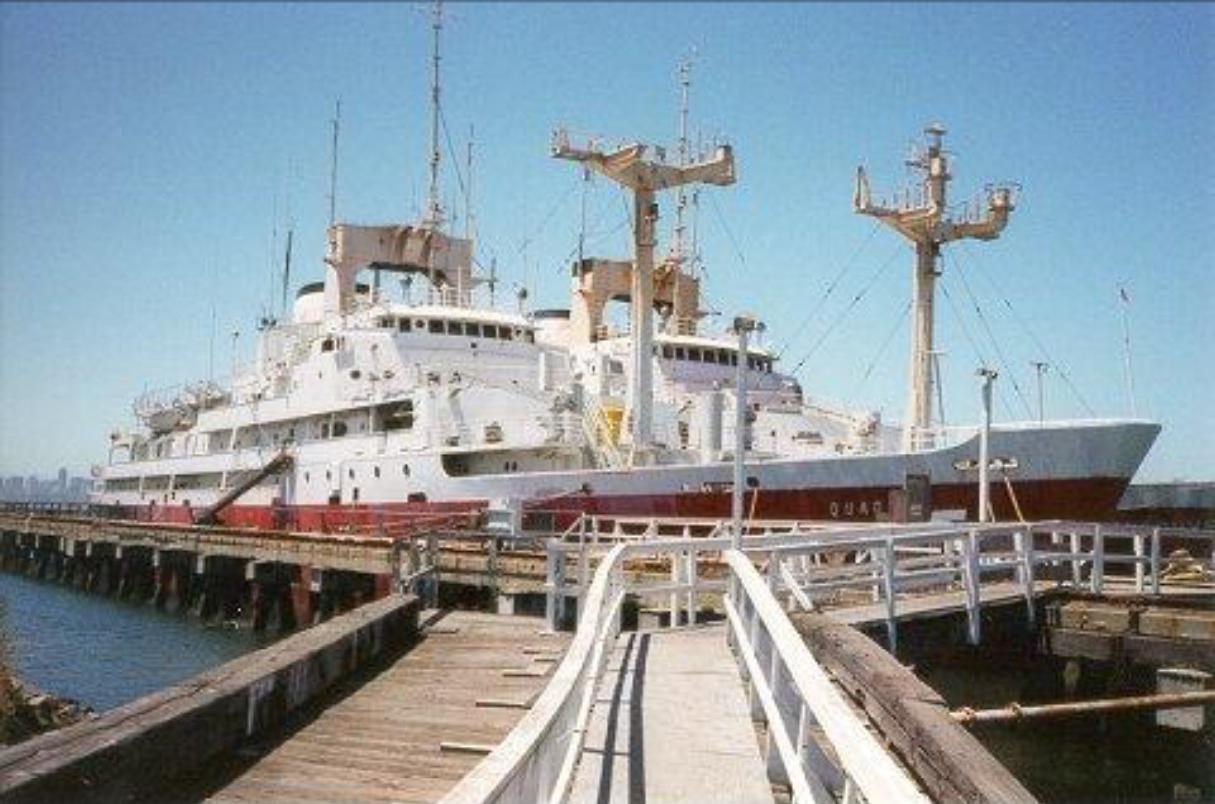

| 1990's. After being taken out of service in 1981, Vancouver

and Quadra await their fate at a dock in San Francisco. Note the missing

radomes and AN/FPQ-10 radar antennas. (Photo by Ted Severud) |

In their half century of ocean station operations, weather

ships became an epoch of maritime history. They filled a niche in

meteorology, oceanography, national defense and safety at sea. The

ships are now gone; the ranks of the pilots who flew over them and

the crews who sailed in them are fewer each year, but their role in the

lore of the sea will remain forever.

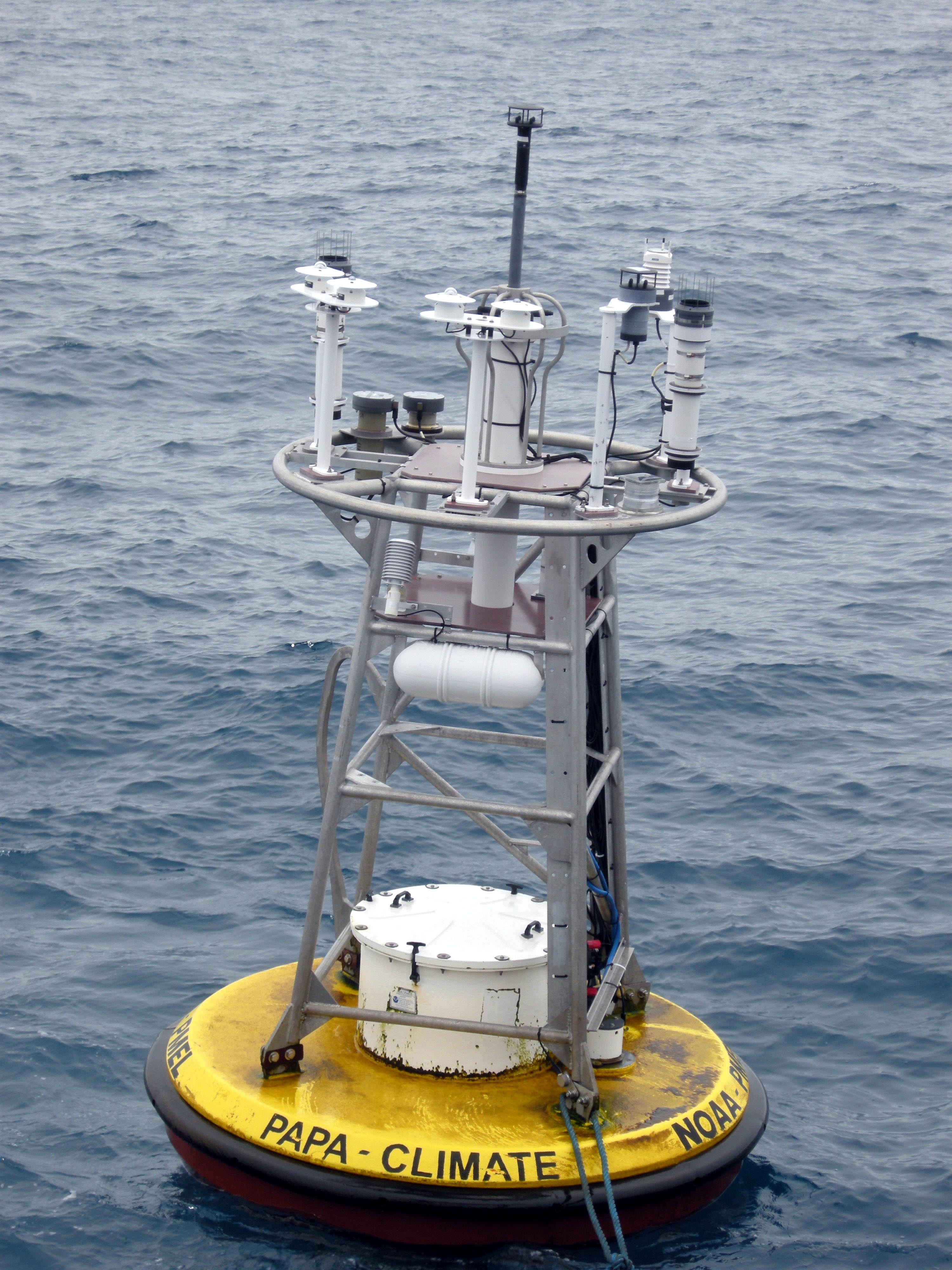

SO WHAT HAPPENED NEXT?

As time marched on, newer methods to collect weather data were developed.

Weather ships were very expensive to operate so over time, they were all

taken out of service to be replaced by data gathering buoys.

With the advent of satellite comms, the Weather Ship programs

were discontinued, and after August 1981, shipboard measurements along

Line P were conducted by the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans

(DFO). The Line P program denotes locations between Ocean Station Papa

and the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Along its length are

locations where the Fisheries ship would stop and cast instrumentation

and nets over the side. These measurements were limited to three

to six times per year, and can be found on the Line-P Program web site.

Over the years quite a volume of information had been collected. In 1997-99,

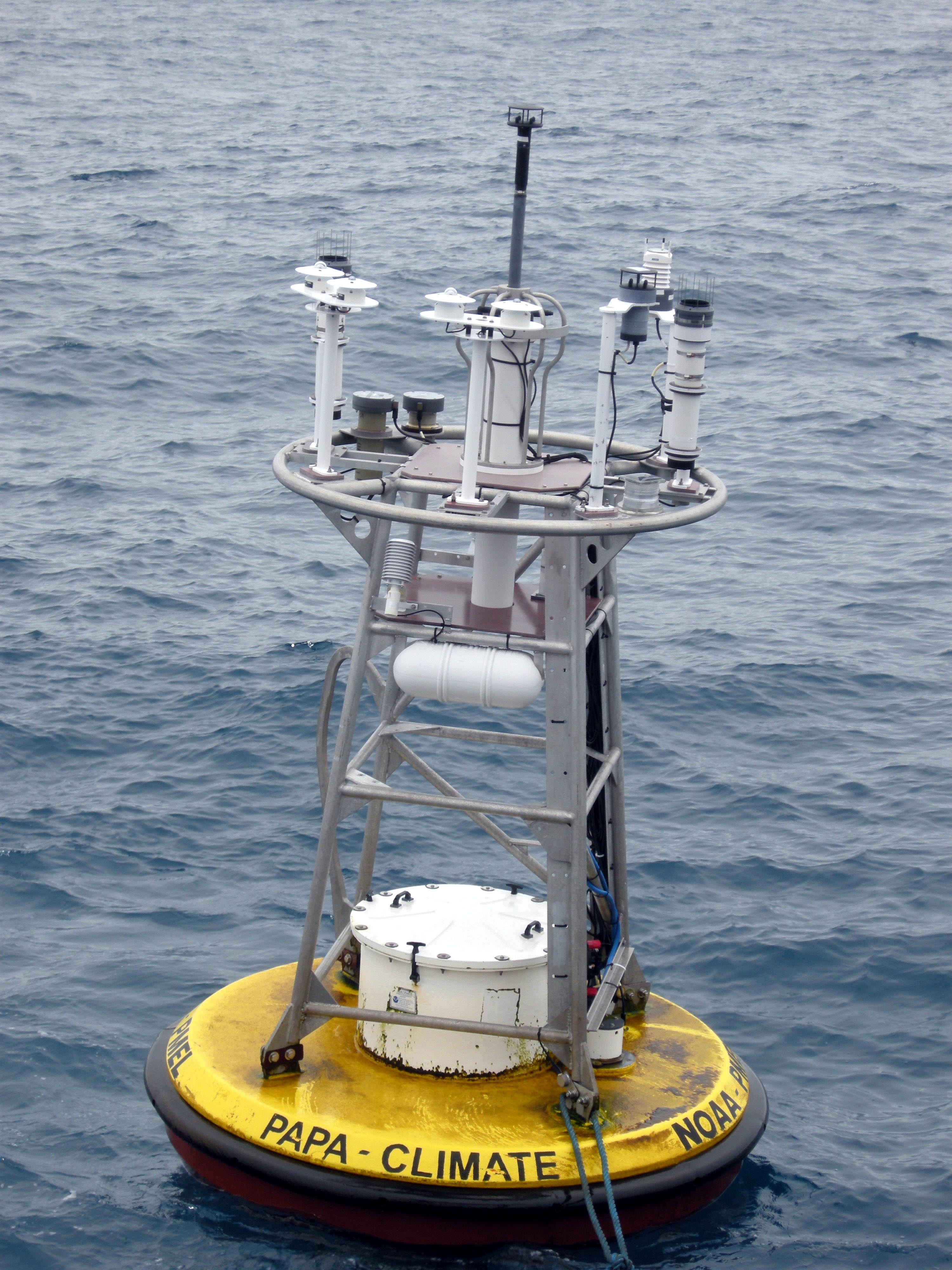

a NOAA PMEL surface mooring was deployed at station Papa as part of the

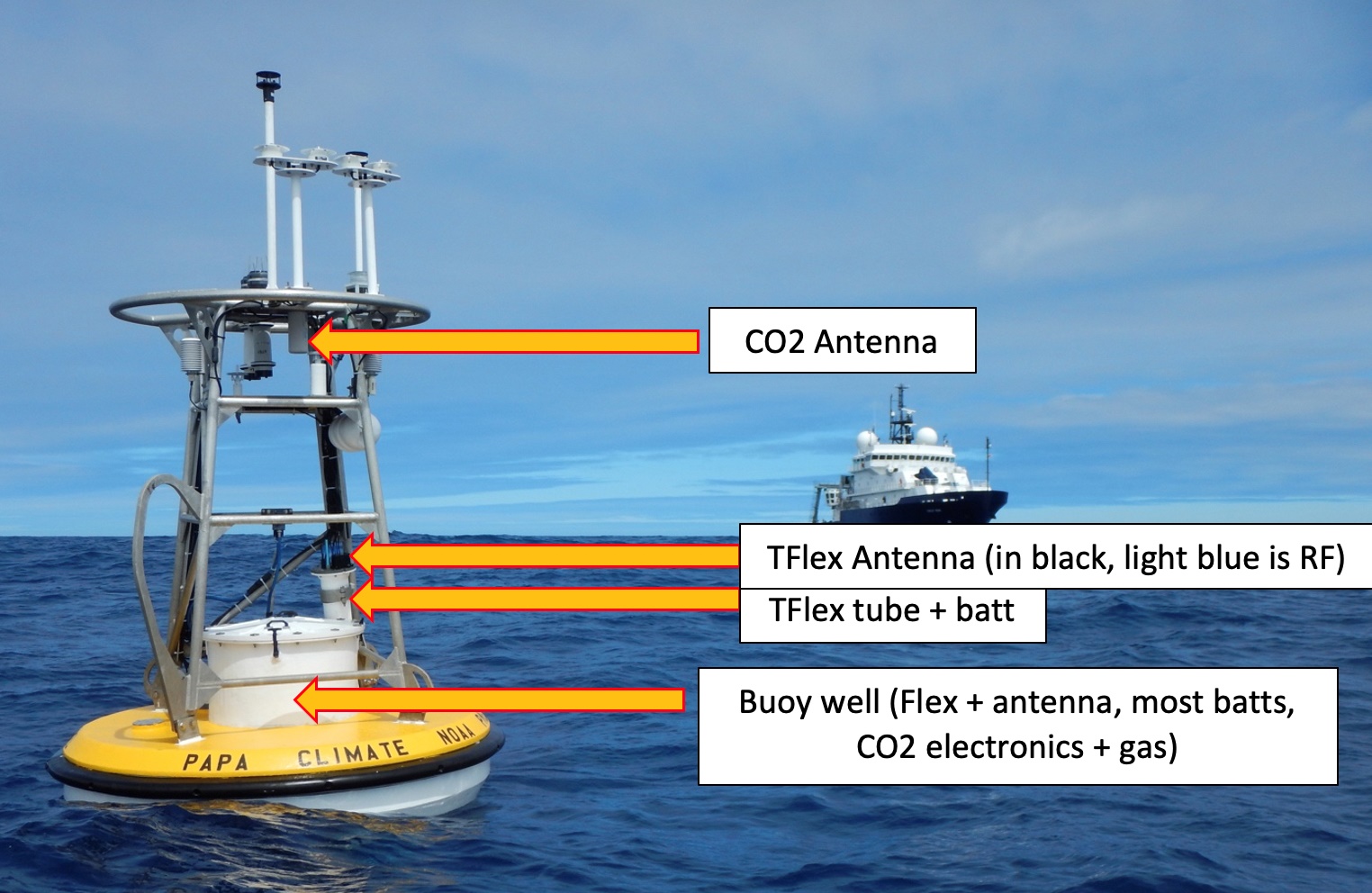

Nation Ocean Partnership Program (NOPP). Starting first, in June

2007, automated observations from the PAPA buoy are being recorded

by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (NOAA). Data is

sent via the Iridium satellite from the acquisition systems deployed on

the buoy These systems are known as "Flex", "TFlex", and "CO2"

depending on the vintage of the buoy.

OPERATING PARAMETERS

Nominal Location of the buoy : 50.1°N, 144.9°W

Mooring Type: Taut-Line

Watch Circle: 1.25km Radius

Scope: 0.985 (2007 - 2014) 0.965 (2015

- Present) See Taut Line Design (below) for explanation.

Avoidance Area: Ships working in the area are requested to observe

an avoidance area of at least 3 NM radius (5.5 km) from the stated anchor

position.

Servicing interval: Annual. The Canadian Department of Fisheries and

Oceans Line-P program continues to provide ship time for annual mooring

maintenance.

The cruise to service the Ocean Station Papa buoy is an

eight day trip out with four days on station and five days for the return

trip, Bad weather can increase the duration of the total trip duration.

During the outbound leg of the cruise, the supply ship stops at multiple

"stations" to perform water sampling from the surface down to depths of

1828 meters (6,000 feet) At the sane tine all the sensors and data

gathering systems aboard the buoy are checked.

|

|

|

| Here. the PAPA buoy is being retrieved for servicing

in 2009 . It is moored to the sea floor by a composite mooring line. The

first 325 meters is wire cable followed by 3,685 feet of nylon rope.

Depicted, is the ATLAS data acquisition system sensors. An ATLAS buoy,

is characterized by the large cylindrical encasement centered at the top

of the buoy. Click on image to enlarge. (Pacific Marine Environmental

Laboratory photo) |

Deploying the buoy anchors. There are actually

two anchors in the photo but one is hidden. Anchors are made from recycled

train wheels. Click on image to enlarge.

(NOAA image) |

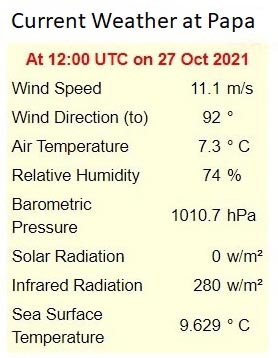

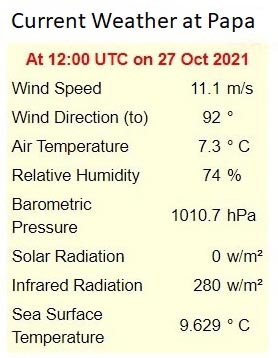

These are real time measurements as transmitted

by the buoy. Other measurements are also being made but not shown here.

(NOAA

image) |

|

| Because the PAPA buoy is not anchored to the sea bed, windy conditions

or

sea currents will cause it to move slightly from its initial deployed position.

This graphic illustrates the deviations from initial deployments.

. (NOAA image) |

|

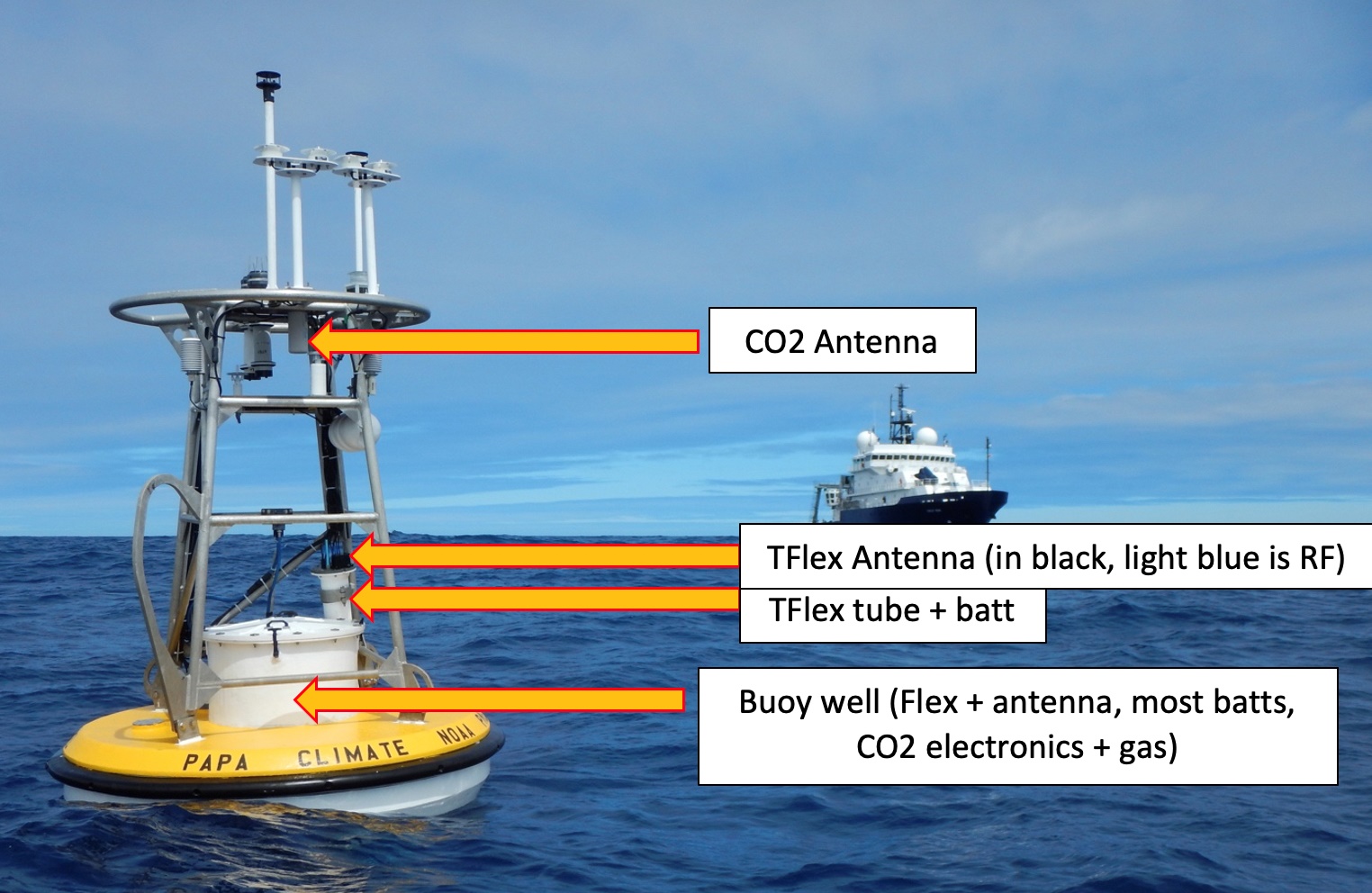

| The Flex system is entirely contained within the buoy well, and transmits

data to the satellite with no exposed external antenna. TFlex, the cylinder

mounted on the side of newer moorings, is similar, but if zoomed in, the

black notch on top (Iridium satellite comms) and the light blue RF antenna

(short range comms) are visible. The CO2 system has a designated

"antenna can" that is mounted near the top of the buoy for improved satellite

transmission. Buoy design changed over the years as newer data acquisition

systems became available. Click on image to enlarge.

(NOAA graphic) |

TAUT-LINE DESIGN

In order to keep the surface buoy close to one nominal position, some

moorings have a mooring length that is shorter than the full water depth.

The ratio of the mooring length to the water depth is called the "scope."

On taut-line moorings, the scope is less than one. This keeps the

line stretched tight, so that instruments on the line do not have much

vertical movement. The OCS Papa mooring uses a taut-line design.

Eight train wheels weighing some 6,850 pounds are used to maintain the

buoy in a taught orientation. Once released the train wheels take

40 minutes to reach the sea floor.

NOAA also employs the Slack-Line Design mooring. In areas where

there are strong currents, the mooring length must be longer than the water

depth. With the longer mooring line, the surface buoy can move over

an area called the "watch-circle." By allowing the buoy to move with

the currents, strain on the line is reduced, which prevents breaking the

mooring line, or moving the anchor.

The composition (ie wire rope, nylon rope, chain) of the mooring cable

can vary depending on the vintage of the buoy. Typically i, it takes 1.5

hours to deploy the nylon portion of the anchor cable. As the anchor drops,

the buoy is pulled across the surface of the sea at speeds of up to 5 knots.

FLEX

The Flex data acquisition system is a custom-engineered system developed

at PMEL. Flex became the primary data system for all instrumentation on

OCS moorings in 2014, though it has been deployed as a secondary system

since 2007, and has been the primary system for subsurface data transmissions

since 2008. Hourly averages of all measurements are returned to shore via

the Iridium satellite. Higher resolution data is logged internally and

downloaded once the mooring is recovered.. Flex is entirely contained

within the buoy well, and transmits to satellite with no exposed

external antenna. Data, downloaded upon recovery, is typically captured

in 10 minute intervals with some exceptions. Data, transmitted over

the satellite limk, 'has an hourly update interval..

BATTERY

The data acquisition systems are powered by a suitably sized, encased

battery pack containing D size cells connected in series/parallel. This

provides approximately 12 to 15 volts of power. The battery

is designed to keep the buoy powered up for at least one year, but

can often last a bit longer.

DEPLOYMENTS

There have been 15 deployments of the PAPA buoy ( https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/ocs/Papa)

between June 7, 2007 and April 25, 2021 all roughly a year apart.

The PA-002 mooring line separated just below the buoy on Nov. 11, 2008

and all subsurface instruments on the wire were lost. The buoy drifted

towards Vancouver Island and was recovered on Jan. 11, 2009.

Ocean Station PAPA is now known as Ocean Climate Station PAPA.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Type 277 was a 10 centimetre surface/low air search set introduced

into naval service in 1944. It was intended for accurate height finding.

Power output was 500 kw. Except for the antennas , it is identical to the

293 set. The weather ships used both the 277P and 277Q sets so that means

aerial outfit ANU or AUK could have been fitted. A detailed description

of the 293 set can be found

here.

[2] VE0MP was formerly assigned to RCMP MACBRIEN when John

Stevens VE1RX was her radio operator. The vessel was in service from 1945

until 1959 and was the former HMCS TROIS RIVIERES.

[3] CCGS Stonetown has a naming anomaly. When the ship was in

commission with the RCN as K531 she was named HMCS Stone Town, the nickname

for St. Marys Ontario. That is the same name that shows up in "Canadian

Warship Names” by David Freeman. After she left the navy, it appears that

the Department of Transport renamed the ship to Stonetown. The ship's bell

from HMCS Stone Town resides in the St. Marys Museum.

Contributors and Credits:

1) Spud Roscoe <spudroscoe(at)eastlink.ca>

2) Frigates of the RCN 1943-1974 by Ken Macpherson

3) MSN Encarta Maps http://encarta.msn.com

4) From America To United States: The History of the

Long Range Shipbuilding Program in the USA- Part 4

by L.A. Sawyer and W. H. Mitchell

5) HMS Collingwood Museum ,Chide, Fareham England.

6) Ships of Canada's Naval Forces (1910-1993) by Ken

Macpherson and John Burgess.

7) Canadian Coast Guard web site. Vancouver/Quadra extract:

http://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/usque-ad-mare/chapter08-09_e.htm

8) Vancouver/Quadra statistics http://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/usque-ad-mare/details_e.asp?Name=Vancouver

9) Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canadian_Coast_Guard

10) Vancouver photo http://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/usque-ad-mare/photos/vancouver2.jpg

11) http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/sci/osap/projects/linepdata/linephistory_e.htm

12) Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/viewImage.do?id=4698&aid=2343

13) Ronald Barrie <BarrieR(at)mar.dfo-mpo.gc.ca>

14) USCG Weather Ships http://www.uscg.mil/history/webcutters/rpdinsmore_oceanstations.html

15) Jack Cain <jccain(at)shaw.ca>

16) Barry Hastings <bhuman(at)shaw.ca>

17) Publication CB 4182/45 Radar Manual (Use of radar)

from 1945.

18) Øyvind Garvik <oygarvik(at)online.no>

19) Merve Huges C P Coaster's [cpcoastr@shaw.ca]

20) Miramar

Ship Index

21) Alexander (Sandy) McClearn <smcclearn(at)gmail.com>

22) Mike Ball <mball65(at)shaw.ca>

23) Frank Statham <fstatham(at)gmail.com>

24) Ocean Station Vessel Manual, 5th Edition 1970.. ICAO

6926-AN/856/5

25) Ted Severud <severud(at)telus.net>

26) VE0MC QSL card - Bill White marscan1(at)gmail.com

27) PAPA buoy https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/ocs/papa-background

28) Nathan Anderson - NOAA Affiliate [nathan.anderson(at)noaa.gov]

29) 1953 edition of "Radio Navigational Aids" published

by the US Navy Hydrographic Office

Back to Table of Contents

Apr 1/24